Peace and Disarmament

As a freshman lawmaker, Sissy Farenthold took a principled stand against the Vietnam War. In 1969, she was the only member of the Texas House of Representatives who opposed a resolution commending former president Lyndon B. Johnson for his time in office. As a critic of the Vietnam War, Farenthold couldn’t support the resolution because it included Johnson’s handling of the war.

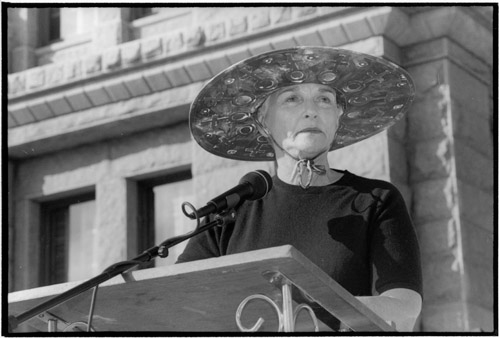

Her anti-war views continued to evolve, taking aim at American foreign policy. On President Nixon’s second inauguration day in 1973, Farenthold delivered a speech at the Houston Peace Rally in which she condemned the administration’s dangerous and costly war leadership. And she denounced American foreign policy as hypocritical: “We cannot remain a free republic at home and an arrogant empire abroad.”

Yet, it was not until 1979, Farenthold later wrote, that she moved beyond what Helen Caldicott termed the “psychic numbing” of the then-impending deployment of nuclear missiles in Europe. Farenthold said a speech by Caldicott spurred her involvement with the international women’s peace movement and opposition to the arms race and the development and deployment of the new generation of weapons.

At the time, the Cold War had not yet ended and women were protesting for peace from Central America to Europe. It was clear that state representatives alone would not bring peace; citizens of opposing countries, especially women, needed to get to know each other and work together for change.

Farenthold spent much of the 1980s collaborating with her cousin Genevieve Vaughan to nurture a movement that was at the intersection of gender, peace and development. International collaboration and exchange were central to their aims. Much of their exchange work was done through or in conjunction with the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), a progressive multi-issue think tank in Washington, D.C. devoted to peace, justice, and the environment. Farenthold joined the board of IPS in the early 1980s and later served as chair of the board from 1986 to 1991.

Vaughan and Farenthold were supporters of IPS’s Third World Women’s Project, and very involved in its activities. The project was started in 1981 by Isabel Letelier, a Chilean exile in the United States whose husband, Orlando Letelier, was the former ambassador to the United States under deposed President Salvador Allende. Orlando Letelier was assassinated with a car bomb by Chilean secret police in 1976 in Washington D.C.

Isabel Letelier started the project to bring women from developing countries for speaking tours across the United States, with an eye toward generating critical analysis of U.S. foreign policy. As one of its documents explained, “Despite growing interdependence between the U.S. and the developing world, most Americans know very little about these countries.”

Over the course of the 1980s, the Third World Women’s Project brought to the US women from Brazil, Bolivia, Jamaica and Peru to speak to women’s groups, community activists, government officials, unions and churches. The speakers were fighting for economic justice and women’s rights in their own countries.

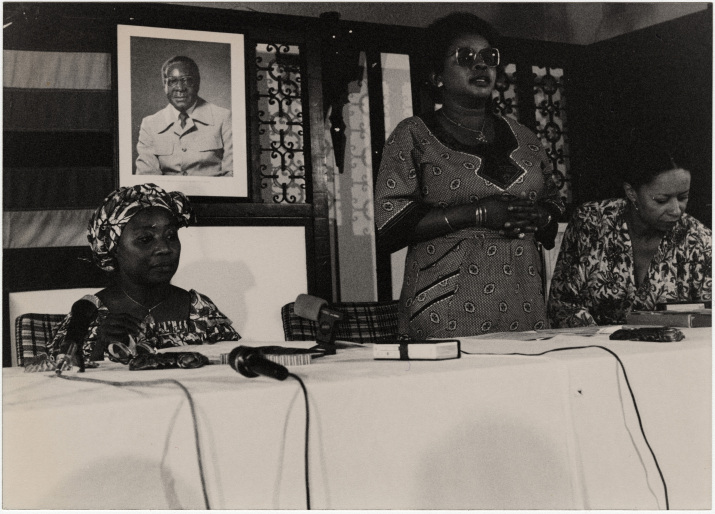

In addition to bringing people to the United States, Farenthold and Vaughan also reached out to women around the world. In November 1982, Farenthold attended the Women in Southern Africa Conference in Zimbabwe. Designed to explore how different institutions affected women’s lives, the conference brought together agencies, organizations, and individuals in Southern Africa to study “strategies for change.” Farenthold later said the conference changed her perspective on women’s issues, as she became more aware of women’s experiences in other countries and the harsh realities of apartheid in South Africa.

In 1983, Farenthold made solidarity visits to anti-nuclear women’s peace camps at Greenham Common, England, Comiso, Italy, and Seneca Falls, New York. In Comiso, she participated in protests, including one scheduled in tandem with the annual International Women’s Day march on March 8. During one of the protests, she witnessed Italian police attacking some of the female protesters.

“One minute, the police were joking with the women protestors. The next minute, the scene turned ugly, and women were being rough-handled by the police,” she said. “I was standing near a woman whose arm was broken as it was twisted by a policeman. I heard the snapping of the bone. And I still hear it. … This was actually my first experience with unprovoked official violence. … I was angry, but powerless.”

In the first part of the decade, Vaughan preferred to stay behind the scenes as an anonymous donor to international women’s peace and development. But in 1985 that changed. Along with several other activists in the international women’s movement, Vaughan and Farenthold helped to conceptualize the Peace Tent in Nairobi, Kenya at the NGO Forum held in conjunction with the third United Nations World Conference on Women.

“The Peace Tent is the international feminist alternative to men’s conflict and war,” according to an official statement released by the organizers. “It is the place where finding peaceful solutions to conflict, both in personal lives and in the public arena, is the priority. The opportunity is for every woman’s voice to be heard.”

In a speech titled “Women’s Search for Peace,” which she delivered at the Federation of Houston Professional Women in 1988, Farenthold recalled that the Peace Tent was a forum for women from around the world to speak about their experiences with war and violence. Though women from warring countries had heated debates over the course of the Peace Tent meetings, participants maintained civil dialogue and collaboration, and expressed themselves through art and culture.

Farenthold and Vaughan continued their work by helping to found Women for a Meaningful Summit (WMS) an ad hoc group of women’s organizations and individuals brought together to ensure women’s voices were represented at the Reagan-Gorbachev Summit Meetings in Reykjavik, Iceland, in 1986. The meetings represented a turning point in U.S.-Soviet relations and the nuclear arms race, and WMS worked to establish a larger role and greater influence for women throughout the decision-making process surrounding nuclear weapons.

A year before the summit, Farenthold was part of a delegation, including the Rev. Jesse Jackson Jr., that met with Mikhail Gorbachev in Geneva to urge support for a comprehensive nuclear test ban treaty and that resources spent on nuclear arms be directed to ending world poverty. In a Dec. 3, 1985 report to IPS, Farenthold noted that the meeting went over its allotted time. But she also noticed something else: Like President Ronald Reagan, Farenthold wrote, Gorbachev also was surrounded by male advisors.

In 1986, Farenthold stood outside the Reykjavik summit with a banner that read “U.S. Citizens for the Test Ban.” Long after the Cold War ended and the nuclear freeze movement waned, she continued to speak out against the dangers of nuclear proliferation. And she remained a voice for peace and for an American foreign policy that supports democracy and social justice around the globe.