Dirty 30

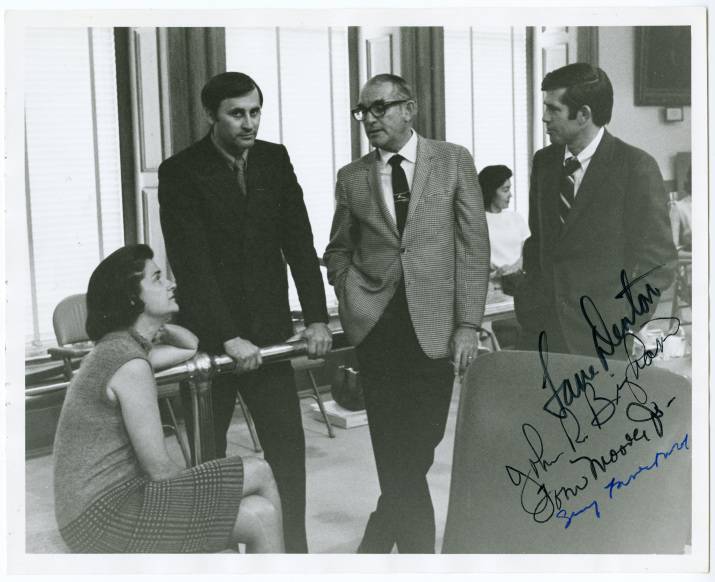

During her second term in the Texas Legislature, Sissy Farenthold became a formidable opponent of special interests as the self-described “den mother” of a coalition of political reformers known as “the Dirty Thirty.”

The band of Republicans and liberal Democrats rocked the state political establishment when they called for an investigation of Speaker of the House Gus Mutscher, who was named with Governor Preston Smith and other Democratic elected officials in a federal bribery-conspiracy case. They were accused of supporting legislation in exchange for valuable insurance stocks.

In a 1971 lawsuit, the Security and Exchanges Commission (SEC) claimed that Frank Sharp, the founder of Houston’s Sharpstown State Bank, had arranged more than half a million dollars in loans for stock purchases for Smith, Mutscher, House Appropriations Chairman W.S. “Bill” Heatly, State Representative Tommy Shannon, and others. In exchange, in September 1969, they helped pass two bills designed to allow the bank to escape federal regulation. The lawmakers later sold the stocks at a considerable profit.

The bills were never signed into law. Governor Smith vetoed them under pressure from state bankers who opposed the legislation. In January 1971, however, the failed legislation caused a public stir when the SEC lawsuit was reported. Yet, statehouse leaders ignored the allegations and continued with business as usual.

The Dirty Thirty made the lawsuit a political issue by calling for an investigation of Speaker Mutscher. The significance of the group’s action is best understood in the context of the culture of secrecy and favoritism in state government at the time. Testimony before committees was recorded at the pleasure of chairs. Legislation was often approved with little, if any, discussion on the House floor. The Speaker of the House lavished favors on special interests and fellow lawmakers through appropriations bills.

Farenthold had authored bills requiring committees to record testimony and limiting the Speaker of the House to one two-year term. Both bills were defeated, but her efforts made her a natural choice to carry the torch for the Dirty Thirty. “With all respect to her colleagues, this was Sissy’s movement,” Ronnie Dugger, founding editor of The Texas Observer, would later say.

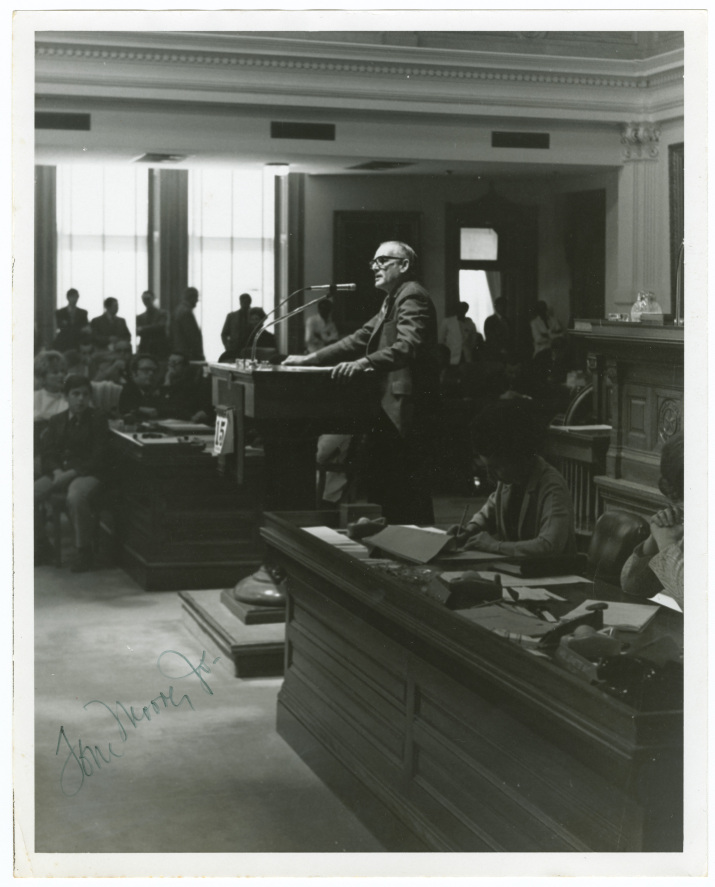

In March 1971, she introduced House Concurrent Resolution 87, also known as the Farenthold Resolution, calling for an investigation into the SEC allegations against Mutscher. The resolution had 22 co-sponsors, but supporters knew the House leadership would send it to a committee to die quietly. So, using a parliamentary tactic called “privilege of the House,” they attempted to force a vote on the floor. This parliamentary tactic allows lawmakers to call for immediate consideration of issues that challenge the integrity of the House and its members.

At first, Mutscher denied Farenthold’s request to address the House, but Representative Lane Denton, D-Waco, appealed the Speaker’s decision. Ten other representatives seconded his appeal, forcing a House debate on the decision. Then, Representative Tom Bass, D-Houston, told Mutscher that the rules dictated that he leave the chamber while the matter was being debated. It was the first time Mutscher had been forced to leave the House, according to former representatives.

Three hours later, lawmakers voted 118-30 to sustain the Speaker’s decision, defeating Farenthold’s resolution. Following the vote, a lobbyist allied with Mutscher muttered, “those thirty dirty bastards.” The name stuck. “We just dropped the ‘bastards,’” Farenthold said.

Though the resolution was defeated, it had succeeded in highlighting a scandal that state officials wanted to ignore. In response to a public outcry over the matter, Mutscher eventually created a committee to investigate the allegations in the lawsuit, but he stacked it with his supporters. No one was censured.

The Dirty Thirty paid a price for challenging the legislative leadership. Their bills often died in committee, and they were the targets of punitive legislation. During the state’s decennial redistricting process, the districts of Farenthold and other members of the coalition were eliminated, or redrawn to make reelection bids difficult.

Still, letters to the editor, student rallies, and even folk songs praised the group as heroes, and attacked their nemeses in the Legislature as agents of big business. And candidates in the 1972 legislative races sought the group’s endorsement.

The Dirty Thirty ultimately made state government more transparent and ethical. By the time Farenthold left the Legislature in 1972, Texas state government was poised for change. A new crop of Republican and liberal lawmakers swept into office in the 63rd Legislature[Symbol]half of the members were new[Symbol]and soon passed open meetings and open records laws inspired by the spirit of the Dirty Thirty.

Emphasizing Farenthold and the Dirty Thirty’s impact, Terry O’Rourke, a legal strategist for the coalition, said, “Today every level of government operates with open meetings and a public information act, and that would not have happened but for their work.”