Texas Equal Rights Amendment

Sissy Farenthold is celebrated for helping pass the Texas Equal Rights Amendment, but when she joined the Legislature, she didn’t support the state ERA.

“I was a dutiful daughter of the State Bar of Texas, and the Bar didn’t support the amendment,” Farenthold said.

Coming from South Texas, she was also isolated from the burgeoning national women’s movement. When Farenthold authored a bill during her first term to create a statewide human rights commission to address discrimination, an adviser had to suggest that she include gender discrimination.

Before the end of her first term in the Legislature, however, Farenthold had broken with the Bar’s stance on the state ERA and become an advocate for the amendment. The organization had long argued that discrimination against women could be addressed through statutes rather than a constitutional amendment. To make its point, the Bar had helped craft a 1967 law that granted married women the right to own and manage property independent of their husbands.

Farenthold began to question the Bar’s position on the state ERA when a representative of the organization spoke to the House constitutional amendment committee, of which she was a member. She described the group’s reasons for opposition as “vacuous.” Later, Farenthold was reminded that the Bar had also opposed women serving on juries “because they would be too worried about their children” and unable to focus on the trial, she said.

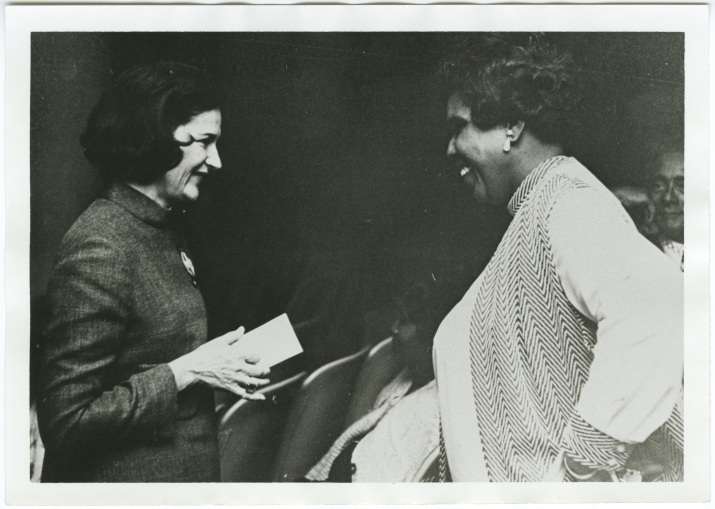

When state rep. Rex Braun, D-Houston, introduced the bill in 1971, Farenthold co-sponsored the legislation. Barbara Jordan co-sponsored in the Senate. The bill cleared the Legislature, and Texas voters approved the state ERA in a constitutional amendment election in November 1972.

The Texas Equal Rights Amendment was distinct from the federal ERA. The state amendment was first introduced in the Legislature more than a decade before Congress passed the federal ERA in 1972. The state effort was the work of the Texas Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs and its past president, Hermine Tobolowsky, who is called “the mother of the Texas ERA.” Tobolowsky, a Dallas attorney, lobbied lawmakers and famously challenged the Bar’s opposition to the amendment in a 1967 editorial in the Texas Bar Journal.

The same year the state ERA was approved by voters, Texas lawmakers ratified the federal ERA. Passing the federal ERA later became one of Farenthold’s priorities when, as first chair of the National Women’s Political Caucus, she campaigned vigorously for its ratification. The measure ultimately failed to get support from the necessary 38 states by the ratification deadline to amend the U.S. Constitution.

Farenthold’s “evolution,” as she called it, on the state ERA said much about her political values. As a new lawmaker she was focused on economic rights for poor women, in line with her experience as a legal aid attorney in South Texas.

An article in the Dallas News on Jan. 15, 1969 about Farenthold and Jordan, the only women in the Legislature at time, noted that women’s rights were “low on the list of priority legislation for both women.” Based on her support for the state and federal ERAs, however, when Farenthold ran for governor in 1972 she had become a symbol of women’s rights, and the media had deemed her a “women’s libber.”