Vice Presidential Nomination

At the 1972 Democratic National Convention, Sissy Farenthold placed second in a field of seven candidates for the vice-presidential nomination. The showing was both a testament to her national profile following her hard-fought Texas gubernatorial race and a result of new party rules that gave women and minorities more power at the convention.

A change in the delegate selection process for the convention required state parties to make “reasonable efforts” to recruit women and minorities in proportion to their percentage in the state population. The results were significant. Women constituted 40 percent of the delegates, up from 13 percent at the 1968 convention. And for the first time Farenthold was able to attend the convention as a delegate, she said. State party bosses, like the men she had challenged in the Texas Legislature, no longer had exclusive control over who could attend.

In addition, conventions had not yet become televised coronations of predetermined candidates. So women’s groups and others were able to maneuver on the convention floor on behalf of their candidates.

This heightened role for women at the convention, which was held from July 10-13 in Miami Beach, Florida, came as they were entering a new period of political activity. About a year earlier, the National Women’s Political Caucus had been founded at a conference in Washington, D.C. And Brooklyn Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm was running for the presidency, the first African American from a major political party to run for the position.

Farenthold was recruited to run for the vice presidency when Chisholm, who didn’t have the votes to win the presidential nomination, turned down the Caucus’s offer to back her as vice president. Farenthold had attended the convention as the leader of the Texas delegates for U.S. Sen. George McGovern, who went on to clinch the party’s presidential nomination. But it wasn’t the first time her name had been mentioned for the vice presidency. Before the convention, a handful of students from Baylor University in Waco, Texas, had circulated a national petition to nominate her, and they brought 2,000 “Sissy for VP” posters to Miami Beach.

The campaign for vice president was a rushed three-day affair. A team was quickly formed. Farenthold’s campaign committee officers were Drue Pollan, Bob Bass, and Larry Patty, all Texans. Former Texas Observer editor Larry Goodwyn, who was at the convention to support presidential candidate Terry Sanford, became Farenthold’s speechwriter.

Her announcement to the media gathered in the lobby of the Doral Hotel, headquarters for the McGovern campaign, addressed gender head on: “One avenue open to victory is unique to my candidacy. As a woman, I alone could appeal to the women of all parties. By November 1972, the women voters of this country will outnumber the men by a margin of 8 million votes. Women will probably remain the voting majority for the rest of the century. I believe it is time this majority has representation at all levels of government, including the Democratic Vice-Presidential nominee.”

After the announcement, Farenthold, U.S. Rep. Bella Abzug of New York, Gloria Steinem, founder and editor of Ms. magazine, and Betty Freidan, author of “The Feminist Mystique,” met in the ladies room of the hotel to choose who would nominate her on the convention floor. The ladies room was the only place where they could avoid the mostly all-male press corps, Farenthold said.

The group decided that Steinem would nominate Farenthold. Fannie Lou Hamer, the African-American organizer from Mississippi whose protests at the 1964 Democratic National Convention forced the state to end the practice of sending a white-only delegation to the national convention, would second the nomination, while Allard K. Lowenstein, a former U.S. representative from New York who led the 1967 “Dump Johnson” movement, would provide the third nomination.

Farenthold received 407 votes, coming in second to U.S. Sen. Thomas Eagleton in a field of seven candidates. She received little support from the 171 members of the Texas delegation, led by Dolph Briscoe, Farenthold’s competitor a few months earlier in the Democratic gubernatorial primary.

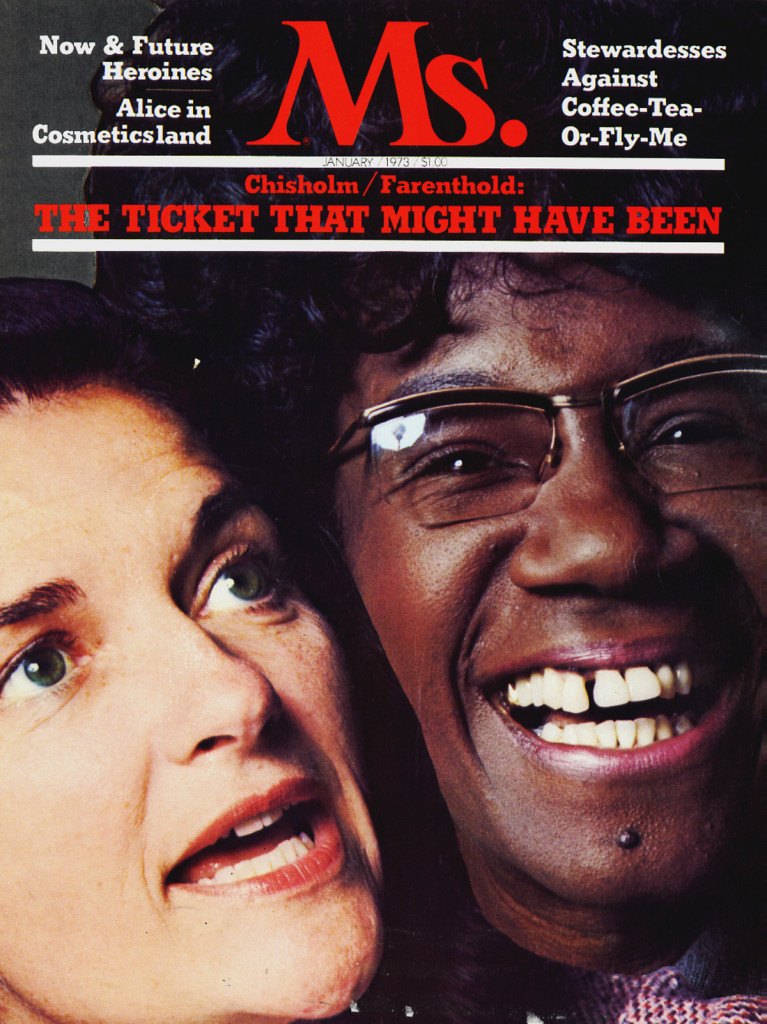

Despite the significance of her nomination, Farenthold later remarked in an interview with Steinem that it was barely mentioned again in the media — with only a few exceptions. In January 1973, Ms. published an image of Farenthold and Chisholm on its cover with the headline “The Team That Might Have Been.”

The article recognized the significant strides both women’s campaigns had made on behalf of women in politics and portended the long road ahead for women to break the ultimate political glass ceiling: the presidency.