Gubernatorial Campaigns

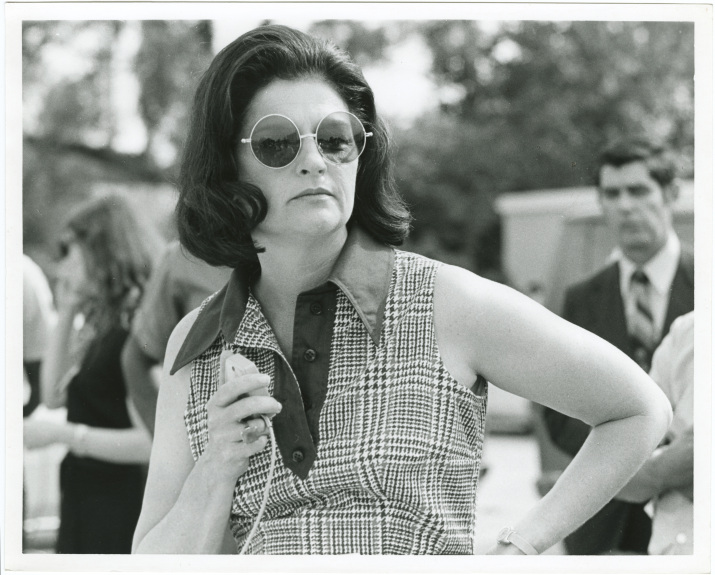

In 1972, as the political fallout from the Sharpstown Bank scandal resonated across the state, Sissy Farenthold launched her first campaign for governor. She hadn’t planned to run for the office, in deference to U.S. Senator Ralph Yarborough, the leader of the liberal wing of the Texas Democratic Party. But when he decided not to run, she entered the gubernatorial race.

Farenthold’s campaign was buoyed by the bank scandal and the ethics reform movement she had led in the Legislature.

“Our present state leaders have run Texas like a cash register,” she said in a TV campaign ad. “The governor profits from the Sharpstown stock swindle. The lieutenant governor makes a fortune on private deals with special interests. Another candidate is a banker who is a back-up man for the big-business interests. It’s time to take Texas from the special interests.”

Farenthold competed against three candidates in the Democratic primary for governor, including a favorite of the state Democratic machine—Lieutenant Governor Ben Barnes, a protégé of former Governor John Connally. Barnes commanded the state Senate during the Sharpstown scandal. He was not implicated in the case, but his association with the politicians linked to the scandal tainted his reputation. The other candidates were Governor Preston Smith, who had profited from the stock deal, and Dolph Briscoe, a businessman who was not in state government at the time.

Farenthold shocked political observers when she outpolled Barnes and Smith, and forced Briscoe into a runoff election. Briscoe defeated Farenthold in the runoff with 54 percent of the vote. But “That Woman,” as critics called Farenthold, had established her political drawing power with 46 percent of the vote.

Her strong showing was no small feat given her scrappy campaign, which was run by Creekmore Fath, a longtime liberal Democrat who had stumped for presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson in Texas. Farenthold darted across the state in an old pastel green DC-3 airplane nicknamed Marilyn, which her cousin owned.

“We usually had just peanuts on board … it was a stripped down campaign in every way,” Farenthold said.

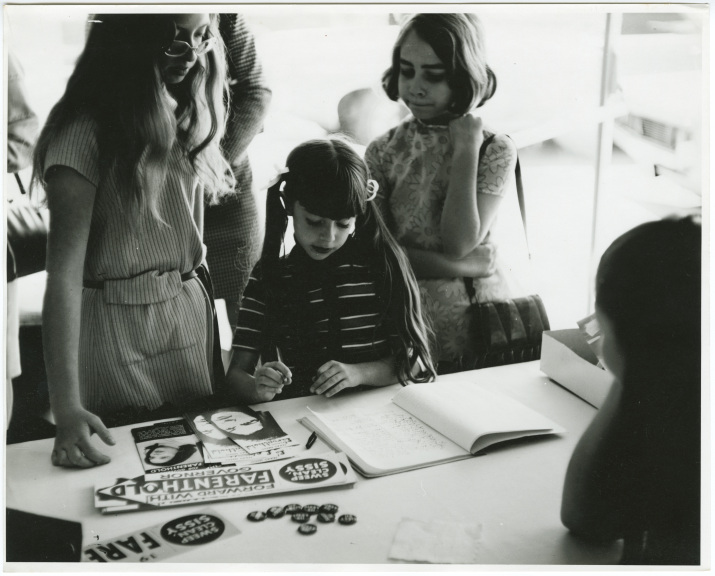

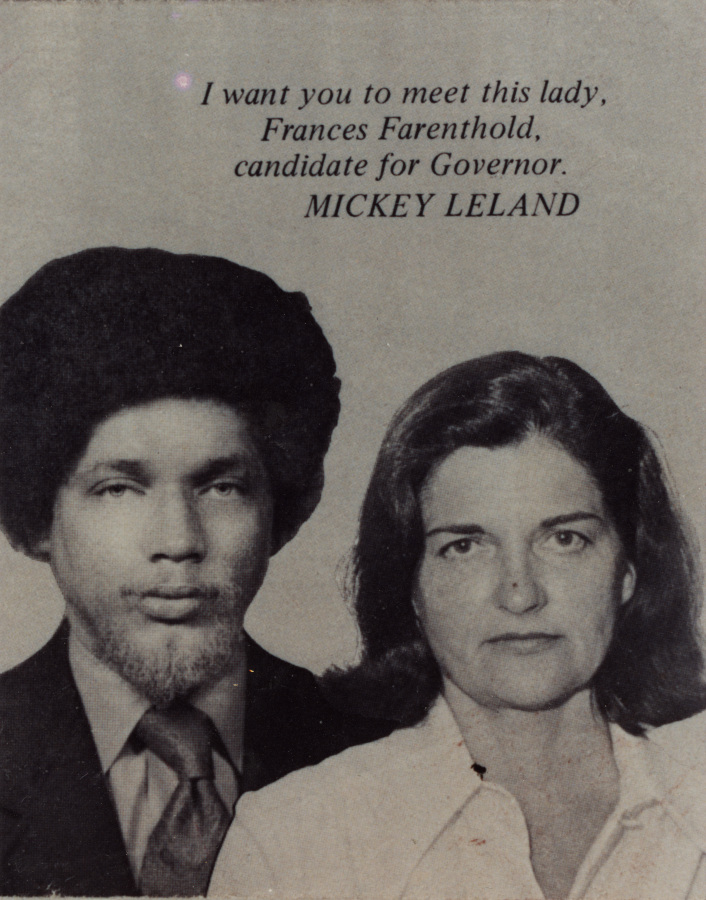

Even though she had no professional public relations team and few paid television or radio ads, Farenthold’s campaign was galvanized by a sense of mission—a desire for a more representative state government. A large part of her base was comprised of youth, African Americans, and women.

“The gubernatorial campaign encouraged women on all levels to take part more in public life. It energized people so much,” said Francie Barnard, who was Farenthold’s press secretary during the campaign. “It just was right as the women’s movement was coalescing.”

Farenthold’s platform included support for ethics reform, open government, civil rights, the Equal Rights Amendment, student representation on the boards of public universities and lowering penalties for possession of marijuana. It also called for disarming the Texas Rangers, the state’s iconic law enforcement officers.

Her son George Farenthold theorizes that if it were not for her stance against the Texas Rangers she might have won the race. The candidate cited other reasons for her defeat. Farenthold said her support for the hot-button issues of busing for school integration and abortion cost her the election.

“I had people come up to me who were supporting me in East Texas and wanted me to oppose busing,” she said. The same was true with abortion, especially in predominately Catholic South Texas, where she grew up.

There were other political factors at play. Ramsey Muñiz, the gubernatorial candidate of the independent La Raza Unida Party, may have siphoned votes from her, said Farenthold, who believed that Latinos were a “natural constituency” for her campaign because of her support for civil rights and her legal aid work in South Texas with Mexican-Americans.

Farenthold became a national name as a result of her first campaign. In 1974, she ran again. By that time, she had been nominated for the vice presidency at the Democratic National Convention, and she was the chairperson of the National Women’s Political Caucus.

Her reasons for running for governor were different the second time around. Farenthold had decided to oppose Governor Briscoe to help shed light on his alleged violations of the state election code, which included allegations that he had taken contributions for the race before appointing a campaign manager.

“Common Cause had come down [to Texas] after I was out of office and had encouraged some reform issues. There was a whole cluster of them. I had nothing to do with them,” Farenthold said. “This particular one said the governor could be sued for campaign irregularities and only one person could sue—and that was the [opposing] candidate.”

Farenthold sued Briscoe for acquiring illegal political contributions for his campaign. The lawsuit came after Briscoe received contributions from a Dallas business executive who falsified the contributions under the names of out-of-state employees. Farenthold ultimately settled the lawsuit with Briscoe in an out-of-court settlement believed to exceed $100,000.

“The press never understood,” said Farenthold, referring to the fight over Briscoe’s campaign contributions. “They thought it was just a notion to get a headline.”

Her second campaign never developed the excitement of her first run. An article in Texas Monthly in April 1974 attempted to explain why. “In 1972 she had going for her some identifiable villains, some clear-cut (and inexpensive) reform issues to expound, and the fresh memory of an appalling scandal to fuel the broad-based political movement which flocked to Farenthold,” Chase Untermeyer wrote. But in 1974, she lacked “a credible bogeyman…Unlike Preston Smith or Ben Barnes, Briscoe [did] not easily conform to the outlines of villainhood.”

Briscoe clobbered Farenthold 70 percent to 30 percent in the Democratic primary and went on to a second term as governor. But Farenthold’s first gubernatorial campaign, in particular, helped dispel the notion that a woman and a liberal could not be a competitive candidate for the top office in Texas.