April 12, 2017

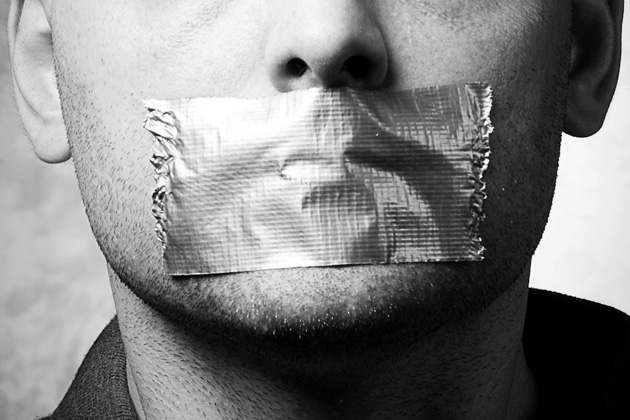

#JungleRepublic: Where a Facebook Status Can Cost You Your Freedom

by Reina Wehbi, an LLM student at Texas Law, concentrating in Human Rights and Comparative Constitutional Law, and member of the 2016-2017 Working Paper Series Editorial Committee.

An enraged young Lebanese activist, Ahmad Amhaz, was detained in March over this Facebook status: “Three kinds of animals currently rule our country: a donkey, a crocodile and a third whose kind is yet to be discovered.” Referencing the Lebanese president, prime minister, and speaker of parliament, Ahmad used the popular social media network to express his dissatisfaction with what he perceives as the “incompetency” of the country’s leaders, using the hashtag #JungleRepublic. After being stopped at a check point by intelligence officers for an alleged traffic violation, Ahmad was driven to a police station where he was later told he was arrested for online libel. Ahmad was then transferred to the Bureau of Cybercrime and Intellectual Property Rights for investigation. One week later, the investigative judge confirmed charges of libel and defamation against Ahmad who was kept in detention. Meanwhile, popular outrage from Lebanese civil society and human rights organizations—including Human Rights Watch and the Lebanese Center for Human Rights—grew stronger, propelling the release of a statement condemning the “arrest, detention and prosecution of Ahmad,” which constituted a violation of Lebanon’s human rights obligations under International Law. The infuriation of human rights defenders led the president and the prime minister to relinquish their personal rights regarding the case and the activist was released on bail after 9 days of detention. However, Ahmad is still on trial and could face up to two years in jail for violating Article 852 of the Lebanese Penal Code, which prohibits defaming the office of the President and national emblems.

The wave of arrests targeting journalists and activists in Lebanon over online statements— especially those made on Twitter and Facebook—during the last few years has escalated at an alarming rate. The Penal Code that the Cybercrime Bureau relies on to prosecute those who commit online libel, slander, and defamation dates back to the Ottoman Era, and thus does not comprehensively cover online crimes, modern norms of free expression and punishable dissemination of information. In the absence of clear law regulating cyberspace, the credibility of the Cybercrime Bureau, which was established by the Internal Security Forces in 2006 following the rise of cybercrimes, continues to be tested. Moreover, the broad and vague language of Lebanese criminal laws allows for discretion in applying the law. The Bureau enforces these vague laws against those with no political power as a way of intimidating the public. The legality and proportionality of pre-trial detention prior to conviction also remains in question and puts at stake the right to due process.

Article 13 of the Lebanese Constitution guarantees freedom of expression “within the limits established by the law.” Although the article seems to protect this basic freedom, it grants public officials immunity against criticism and results in “self-censorship” of journalists, activists and civilians who often use social media to voice their concerns and respond to officials’ activity. Although it is hard to draw a line between protected speech and extreme speech, Lebanon remains in a dire need of updated laws that are compatible with modern modes of communication. In the opinion of the young activist Ahmad, “officials should not be immune to criticism or defamation when they are not diligently serving the public.”