July 20, 2017

Mixed and Clashing Patterns in Fashion and Between Shanzhai Culture and Copyright Law—A Unique Perspective for Women Designers

Sara Liao’s article, “Fashioning China,” delves into the juxtaposition of copyright laws and creative women entrepreneurs in China. Shanzhai culture refers to the detailed-oriented reproduction of clothing, accessories, and other consumer goods. Copyright laws and governmental entities claim these goods are counterfeit and damage the economy. For the women entrepreneurs, however, these reproductions are a source of livelihood and a form of artistic expression. Shanzhai culture promotes an alternative view of their work that does not characterize the makers as criminals manufacturing counterfeits, but as artists creating fashion and as women aspiring to a greater life—the Chinese dream.

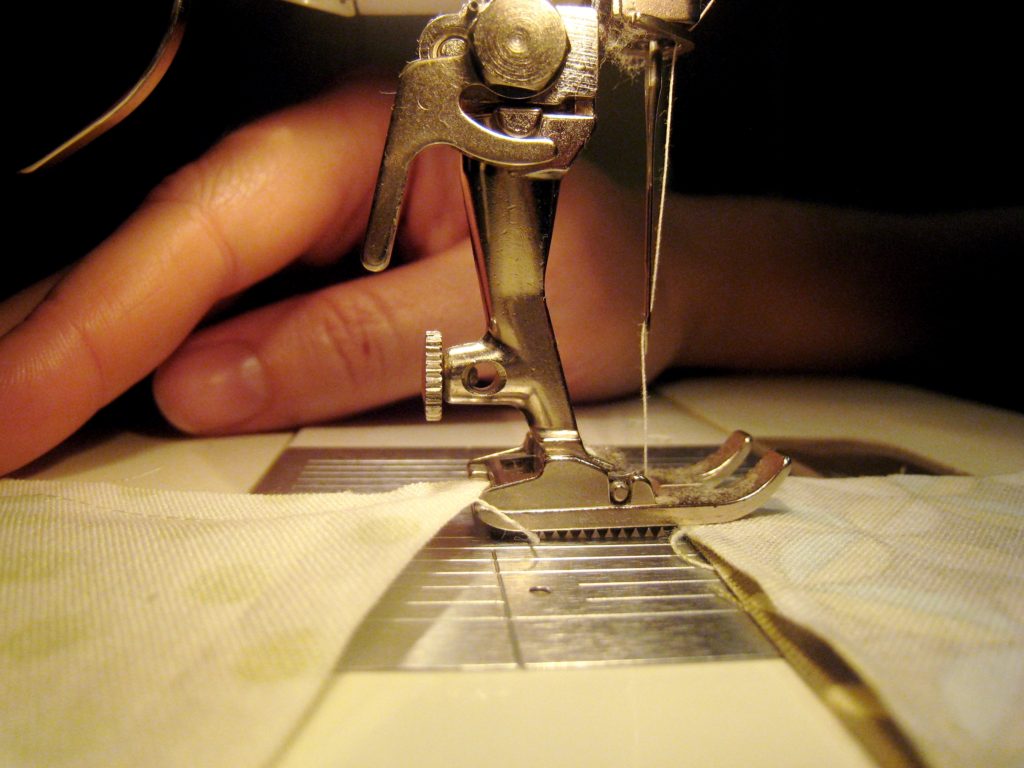

The paper details the design and manufacturing process of reproduction starting with an online polling process and ending with delivery of the reproduced project. The items produced through Shanzhai are not the cheap knock-offs many associate with made-in-China counterfeit products. Instead, these products are intricate. Immense detail is required down to the stitching and attaching buttons to a garment.

The strength of this paper lies in the author’s ability to weave the human element and the true impact on women’s livelihoods into the legal discussion of the government restrictions on counterfeiting. Traditionally, discussion of copyright law and product reproduction are narrowly focused on the economic harm befalling the companies whose products are being reproduced. These accounts are cold and the actors are nameless. Instead, this paper shines light on the faces of the women who create products by giving them space in the narrative. The paper exposes the true complexity of the tension between Shanzhai culture and government regulation and gives the reader room to consider each aspect of the debate.

There are ample opportunities to further this type of research investigating the cultural and political implications of the fashion industry in China and throughout the rest of the world. There is much to be dissected from the growing feminisms of these producers and business women. Further inquiry into the implications of Shanzhai on intellectual property laws and the rights of these property holders would be illuminating to discover the cause of these problems as well as some potential solutions. Where is the exact departure between creative appreciation and a copyright violation? Where exactly will the line for protected speech be drawn? Is it in a designer’s sketchbook or a line in a settlement of litigation? Further research is necessary to advise those who might be trying to bridge these cultural divides to protect freedom of expression as well as protect individual property rights.

Additionally, analysis on free speech issues and expressive product creations could create a wealth of opportunity for scholarly work. This individualistic approach to speech strengthens with the rise of social media. In today’s information age, in this political climate where the internet and e-commerce is itself in a precarious position due to the potentiality of “net-neutrality” policies, and with globalization blending cultures at an ever accelerating rate, speech issues are a “hot” topic.