December 10, 2015

Violence Committed by Americans against (Foreign) Americans

by Barbara Harlow, the Louann and Larry Temple Centennial Professor of English Literatures at the University of Texas at Austin and on the WPS Editorial Committee. She is the author of Resistance Literature, Barred: Women, Writing, and Political Detention, After Lives: Legacies of Revolutionary Writing, and co-editor of Imperialism and Orientalism: A Documentary Sourcebook and Archives of Empire: Vol I and Vol II.

This commentary is in response to Mark Danner’s lecture, “Spiraling Down: Human Rights, Endless War.”

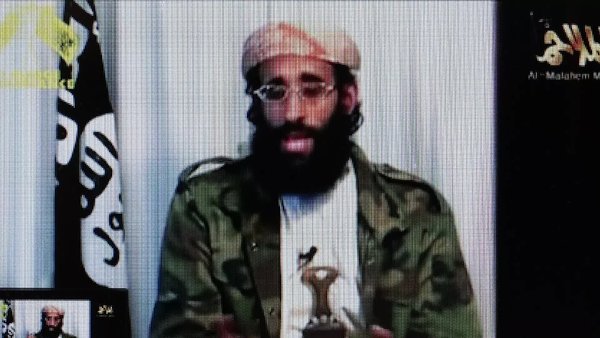

Mark Danner’s portrayal of the muted denunciation of human rights abuses during the now more than decade-long U.S.-led global “War on Terror” and the remission of the once honorable paradigm of the exposure of injustice leading to redress were especially poignant reminders of the current crisis in humanitarian thought and activism. In her post, Natalie Davidson speculates that the lack of public protest and political accountability derives from the fact that the abuses “mainly affect foreigners living outside U.S. territory.” That explanation, however, is complicated, if not obviated, by the death-by-drone of Anwar al-Awlaki (also al-Aulaqi) in Yemen on 30 September 2011. Awlaki, a U.S.-born and U.S.-educated radical Muslim preacher, had been the target of a protracted mission to eliminate him, in an operation code-named “Objective Troy.” In his recent book, which takes its title from that code-name, prize-winning journalist Scott Shane reads that assassination mission to “eliminate” the compatriot as a near-epic mortal combat between the “president” and the “terrorist,” assisted by none other than the “drone.” Barely two weeks after his own violent demise, Awlaki’s teenaged son Abdulrahman was also killed while eating at an outdoor café in Yemen (some say accidentally, others aver the teenager’s alleged own “radicalization” as the rationale), again in a lethal drone strike. He, too, was a U.S. citizen.

In April 2014, the U.S. District Court in Washington D.C. granted the defendants’ “motion to dismiss” in the case of Nasser al-Aulaqi v Leon Panetta et al. (2012). Represented by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), with the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), Nasser al-Awlaqi, father of Anwar and grandfather of Abdulrahman, had charged the named U.S. officials with the unlawful deaths and extrajudicial executions without “charge, trial, or conviction” of his near relatives. The senior al-Awlaki had brought a similar charge in an earlier case against Barack Obama, Leon Panetta (director of the CIA), and Robert Gates (Secretary of Defense) for violations of the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution prohibiting “unreasonable seizure.” His claim in Al-Aulaqi v. Obama (2010) that “targeted killing” of U.S. citizens violated the Constitution had likewise been dismissed, with the Court noting in a lengthy opinion that the plaintiff’s claims raised “non-justiciable political questions.”

The District Court’s repeated, if predictable, dismissals have so far failed to galvanize concerted rejoinders from a larger U.S. citizenry. Yet, the case of Anwar al-Awlaki, the death by drone of the imam and his son, and their elder’s enduring insistence on the rule of law and the integrity of the U.S. Constitution have not been dismissed from either the political annals of contemporary history or their popular cultural re-enactments. In Dirty Wars, Jeremy Scahill’s 2013 monumental account of the construction of “the world as a battlefield” and George W. Bush’s and Barack Obama’s nefarious waging of the “global war on terror,” Scahill interweaves Nasser al-Awlaki’s personal struggle for justice for his son and grandson with what Scahill calls the “story of how the United States came to embrace assassination as a central part of its security policy” and the “story of the expansion of covert U.S. wars.” The latter includes imbroglios that feature “stories of insiders who have spent their lives in the shadows,” or, in the words of Dick Cheney, “on the dark side.” This storied history of Anwar al-Aulaki’s political odyssey and ensuing family saga is also featured in Shane’s Objective Troy (2015). The book narrates the parallel lives of Barack Obama and Anwar al-Aulaki, although, as Shane tellingly if cynically admits in his Prologue, the two “men would never meet, except virtually, clashing in the battleground of ideas, where the cleric’s mastery of the internet would serve his jihadist cause, and violently, when Obama dispatched the drones that carried out Awlaki’s execution.”

Scahill is adamant, even against the opinionated rulings of the U.S. District Court and the apparent lack of interest on the part of Awlaki’s “fellow Americans,” that “Awlaki’s case would cut to the heart of one of the key questions raised by the increasing role targeted assassinations were playing in U.S. foreign policy. Could the American government assassinate its own citizens without due process?” And Shane predicts that Awlaki would become a “bigger brand,” a veritable living legend, given that, as the investigative journalist describes the phenomenon, “One factor in the dark portrayal of drones [is] that stories trump facts in the human imagination, and drone strikes produced compelling stories.”

If the story has not compelled the political or legal change that some might have anticipated, Anwar al-Awlaki’s biographically tragic fate has served, whether in sinister martyrdom or with heroic mien, as legal – and cultural – precedent, as drones themselves are set to become the very stuff of the contemporary international thriller. Indeed, in Drone (2013), the first of political scientist Mike Maden’s fictional Troy Pearce trilogy, the protagonist – a former U.S. government employee and current CEO of a “private security firm specializing in drone technologies” – explains that “a considerable plurality of Americans on both sides of the political spectrum were still troubled by the use of lethal force against American citizens without benefit of trial, whether or not drones were used, even if the threat was imminent and catastrophic.” The same issue, however paraphrased, will haunt Maden’s two subsequent Troy Pearce novels, Blue Warrior (2014) and Drone Command (2015). It also underwrites former National Coordinator for Security, Infrastructure Protection and Counter-terrorism Richard A. Clarke’s Sting of the Drone (2014) and Washington Post columnist David Ignatius’s Bloodmoney: A Novel of Espionage (2012).

It would seem after all, as Natalie Davidson has noted, that if “Danner asks how we can return to legality,” it is all the more the case that “the story he tells can also be understood as one in which law, with its indeterminacy and malleability, its sometimes absurd fictions and bureaucratic vocabulary, plays a key role in reassuring government officials that even acts such as torture and execution are acceptable” (emphasis added). In a world where legal and political discourse are imbued with fictions that enable violence, might fiction ironically be the most promising arena in which to challenge targeted killing?

Perhaps not. Jeremy Corbyn might not write international thrillers but the newly elected British Labour leader did protest strenuously – to the thrill of some of his constituents and the indignant ire of others – the death-by-U.S.-drone of one of his compatriots. Mohammed Emwazi, also known as “Jihadi John,” was slain in November 2015 in the targeted killing of a British citizen, a deed that the nation’s Prime Minister, David Cameron, had condoned as committed in “self-defense.” Cameron’s reference to self-defense echoed the rationalizations of his U.S. counterparts in their rendition of ratiocination in the waging of the “forever war” executed by UAVs (“unmanned aerial vehicles”) or, as some weapons analysts and “whodunnit” fans might prefer, RPAs (remotely piloted aircraft). Whether disarticulated in legal language or spellbound through generic whodunnit intrigues, the questions persist, “loiter” in drone-speak. Might the still muted decibels of denunciation yet become a mobilized chorus of dissent and resistance? What would such a raucous uproar require? And will the culprits at last be brought to justice?