Space is a dynamic, difficult, and dangerous realm.Once the province only of state actors, Earth’s orbit is now open for business. The stakes couldn’t be higher.

Written by Michael Greshko

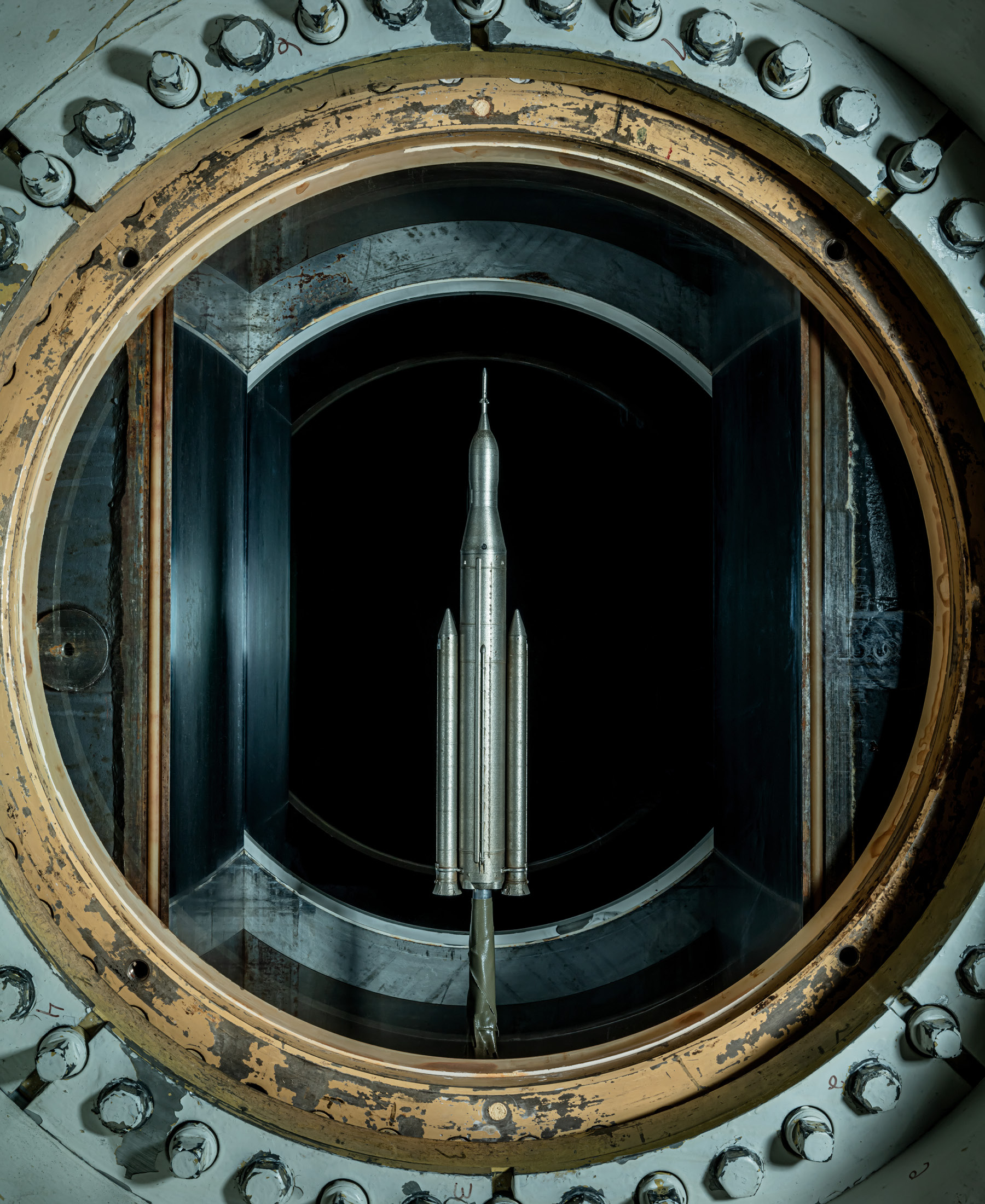

Photos by Dan Winters

Make no mistake:

We are living through the dawn of a second space age.

Thanks to two decades of bipartisan policies, what started more than 60 years ago as a Cold War-era race to the Moon has now become a boon for the U.S. space industry, which is building the technologies and infrastructure required to grow an economy in orbit and beyond.

This gold rush hasn’t just spawned a booming $131.8-billion commercial space industry, accounting for 0.5 percent of the country’s GDP. It’s also setting the stage for a long-term presence on the Moon’s surface. After a hiatus of more than five decades, NASA’s Artemis program plans to return humans to the Moon, as part of a wide-ranging strategy for eventual crewed missions to Mars.

This transformative era is offering lawyers a front-row seat to a host of novel legal issues – not just on terra firma, but in the heavens above. And Texas Law lawyers and students are at the forefront of this literally rocketing industry. “This is an opportunity to get it on the ground of a really exciting field of endeavor,” says Texas Law Professor Adam Klein, director of UT Austin’s Strauss Center for International Security and Law.

Divvying Up Space?

Legally speaking, what even is space? For one, it’s not a specific mile marker. The de-facto international rule, a 100-kilometer altitude known as the Kármán line, isn’t defined in the statutes governing U.S. commercial space activities.

While the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) maintains a list of people who have flown more than 50 miles above sea level on FAA-licensed vehicles, there’s no regulatory change that snaps into place after crossing that line.

Instead, space is treated as a domain governed by international law: in this case, the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 and a constellation of ancillary agreements. Under this Cold War-era treaty, space is free for all nations to explore peacefully. Nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction can’t be put into orbit or placed upon “celestial bodies” other than Earth, such as the Moon. States can’t claim territory in space, either.

If you were to squint and stare at the body of space law from a distance, it would resemble the legal frameworks of other forbidding realms like the high seas or Antarctica. However, space isn’t like any other domain on the planet’s surface. In low-Earth orbit, for example, there’s no equivalent to territorial shorelines. There can’t be. For an object to stay in orbit, it must whiz around the planet at a speed of at least 17,500 miles per hour with no mind to borders below.

So, where do private companies come in? Under the Outer Space Treaty, states are held responsible for any space activities carried out by governmental or non-governmental entities under their control. For instance, when a private American company launches a satellite into orbit, the United States is on the hook.

“It’s based on the idea that a sovereign has responsibilities and liability, but there’s not an idea of ‘dividing up’ space,” says Caryn Schenewerk ’02, who teaches commercial space law and consults with space companies after 12 combined years at SpaceX and the startup Relativity Space.

Patchwork Jurisdictions

Schenewerk, who has written a textbook on space law, notes that our domestic space law has grown out of efforts to enact the Outer Space Treaty. Many federal agencies are involved, including: NASA, the Department of Commerce, and the Department of Defense, all of which commission and operate their own satellites and spacecraft, and contract for commercial space services; the Department of Commerce, which regulates remote sensing of Earth’s surface; the FAA, authorizing commercial launches, reentries, and spaceports; and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), tasked with regulating the satellite frequencies on which practically every space-borne commercial vehicle relies for communication. Under a 1976 agreement, the United States also maintains a national registry of objects that it has launched into space and submits data to a global registry maintained by the United Nations.

But the heart of the industry’s rapid growth, an expansion that’s testing legacy regulations as never before, lies with a monumental legal experiment NASA launched 20 years ago with a program known as Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS). Essentially, NASA changed the rules of the contracting game under the Federal Acquisition Regulations. Two decades on, NASA’s experiment is quite literally shooting for the Moon.

Before COTS, NASA relied primarily on cost-plus contracts. In these arrangements, the federal government controls the spacecraft’s design and operations and then owns and operates the hardware the contractor produces. The Apollo missions and the Space Shuttle were built on cost-plus contracts. NASA controls the minute specifications and safety measures, but as the sole buyer for a one-of-a-kind product, NASA covers vendors’ overruns – and the contractor is guaranteed its costs plus a defined profit.

In 2005, NASA created COTS as a cost-saving, public-private partnership that helped private companies develop their own rockets for resupply missions to the International Space Station (ISS). COTS relied on milestone-based, fixed-price contracts. In exchange for lower, fixed costs, NASA relinquished ownership of the hardware, gave vendors more leeway to meet specifications, and incentivized vendors to contain their costs and find viable markets for their products.

Through 2013, the U.S. government invested $788 million into COTS, funding contracts with Orbital Sciences (now part of Northrop Grumman) and SpaceX, which at the time was a plucky startup. At press, these two companies have flown 48 successful resupply missions to the ISS and have saved the U.S. government billions of dollars in the process.

In 2010, Congress extended the COTS experiment to the highest stakes yet: flying astronauts to the ISS as a replacement for the soon-to-be-retired space shuttle. Under this program, SpaceX has flown 34 NASA and international astronauts to the ISS since 2020. “The arc of where we are today is the story of key decisions to support the commercial space sector,” says Schenewerk.

Classroom of the Cosmos

In addition to courses, Texas Law students explore opportunities in space law through the Texas Space Law and Policy Society (TXSLAPS). Daniel Michon ’20, now an attorney at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, helped form the student group in 2019. He and other founding members “recognized an opportunity to establish a dedicated community of interested law, public policy, and engineering students who had either a passing or professional interest in space-related fields,” says Connor Madden ’23, a former TXSLAPS member now clerking for the Supreme Court of Texas. To Madden, TXSLAPS is “a perfect example of how Texas Law empowers its students to pursue their niche interests.”

Last year, current TXSLAPS president Brittany Silvester ’25 was named a Brumley NextGen Graduate Fellow for Space Safety, Security, and Sustainability. Her research under the program — mentored by Moriba Jah — led to Silvester presenting at a 2024 conference hosted by the International Academy of Astronautics. She also received the Strauss Center’s inaugural Aerospace Policy Solutions LLC Award in Space Policy.

“As soon as I saw the Hubble Telescope images as a kid, I was hooked,” Silvester says. “Fast-forward to today, I’m still a pretty big space fanatic. But now, instead of satiating my curiosity with sci-fi movies, I turn to academia to research questions that excite me.” –MG

The Industry Matures

The space industry now finds itself maturing, with new companies trying to differentiate from established players. “Along comes SpaceX, and they come and prove that commercial space is really where it’s at – they were obviously the groundbreaker,” says Idris Motiwala ’16, an associate at Crowell & Moring who has worked extensively with space companies. “They laid the groundwork for others to follow.”

Many of these companies call Texas home. According to a 2024 report from the office of Texas Governor Greg Abbott, more than 2,000 aerospace entities do business in the state, along with 18 of the 20 largest aerospace manufacturers, and employ more than 154,000 people. Those companies include SpaceX, whose Starship rocket is being built at the company’s “Starbase” facility near South Padre Island, and Blue Origin, whose suborbital New Shepard rocket launches from West Texas.

Firefly Aerospace, a startup headquartered in Cedar Park, TX – where Motiwala, just two years out of law school, served as in-house counsel from 2018 to 2022 – is building smaller rockets in hopes of providing cheaper, dedicated launches for small satellite needs. Firefly is also getting into the lunar game with its Blue Ghost lander set to carry NASA instruments to the Moon’s surface later this year. Other startups like the California-based firm Relativity Space – where Schenewerk worked as a vice president from 2020 to 2023 – are advancing 3D-printing technologies. To test its latest rocket design, the company will attempt its own commercial Mars mission planned as early as 2026 in partnership with the startup Impulse Space.

These and other companies now play a critical role in NASA’s Artemis program – both a cost-saving measure on the agency’s part and an audacious bet on the industry’s ability to develop an economy on and around the Moon. When NASA astronauts touch down on the Moon’s surface during the Artemis III mission possibly as soon as 2026, their ride will be a lander owned and operated by SpaceX. When those astronauts walk the lunar terrain, they’ll be wearing spacesuits made by Axiom Space, a Houston, TX-based company that has flown three commercial missions to the ISS. And as soon as 2030, Artemis’s next moon landing during the Artemis V mission will come courtesy of a vehicle owned by Blue Origin, which is owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos.

This public-private partnership is meant, in part, to serve a broader goal: making Artemis sustainable in a way that Apollo never was. Inextricably tied to the Cold War, Apollo was a race to the lunar surface. But races, by definition, end – and to get to that checkered flag, the Apollo program cost more than $280 billion, adjusting for inflation. With Artemis, NASA is trying something more ambitious: a politically and financially durable moon program that not only sends crews to the lunar surface but equips them – and us all – to return again and again.

Amid all this activity, space lawyers face a diverse list of issues that stem from companies’ attempts to adhere to regulations that were once just the domain of federal agencies. Rocket launches and capsule reentries must be licensed and permitted at ever-growing numbers and ever-growing speed. Compliance strategies for the U.S.’s strict export controls on aerospace technologies must be developed and adhered to. Land use and economic development agreements must be ironed out for spaceports and other facilities.

“In general, the underlying laws were mostly written during the space race,” says Motiwala. “The regulations are being tested by commercial providers now.”

Into the Unknown

This new space race, and the companies now defining it, can also influence security matters around the world. Indeed, the U.S. military’s space budget dwarfs NASA’s entire budget, and the armed forces are an enormous buyer of space services. SpaceX now routinely launches reconnaissance satellites. In September 2023, Firefly successfully completed launch preparations for a military satellite on just 24 hours’ notice, a turnaround that would have been unheard of decades ago.

“Every day with the war in Ukraine, we’ve seen Russian cyberattacks on [commercial] ground stations to disrupt Ukrainian satellite communications,” says Klein, the Strauss Center director. “On the other side, we’ve seen Ukraine benefiting from commercial satellite imagery for its military operations – and arguably even employing, in some cases, an advantage over Russia despite Russia’s space program.”

The increased military use of commercial space – and the broader international reliance on space technologies – raise challenging national security questions. If the U.S. military makes use of commercial satellites, under what conditions could those satellites be targeted legally by an adversary? Is it lawful to conduct attacks using civilian satellites? “There’s a real need for lawyers who have an understanding of the background legal principles – and also the policy context – to go in and serve in these agencies and in these companies,” Klein says.

In part, the Strauss Center is keeping a close eye on these issues through its Space Security, Safety, and Sustainability program, whose lead, Professor Moriba Jah, is a renowned expert on one of space’s biggest emerging problems: How should the world respond to the growing threat of space junk?

As companies take advantage of cheaper and more frequent launches, the number of active satellites orbiting Earth has quintupled in the last five years, from 2,000 to more than 10,000. Tens of thousands more objects at least as big as a cell phone orbit the planet, too. But these objects are merely litter, ranging from discarded rocket stages to the remnants of a 2021 Russian anti-satellite missile test.

Already, the rise in satellite counts has given astronomers headaches and has transformed people’s naked-eye views of the night sky. The risks are more than scientific and aesthetic. If defunct satellites and other forms of orbital debris aren’t responsibly disposed of, they can lead to deadly or disabling collisions between objects in orbit. At worst, clouds of high-speed shrapnel would make it impossible to operate satellites within entire categories of orbits.

“Orbits one day [could] become unusable because it’s a finite resource that’s being exploited without global coordination and planning,” says Jah, who is also an professor of aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics at UT Austin.

Cleanup is possible – but only under the right legal framework. At present, there’s no space equivalent to maritime salvage laws under which private companies can be paid to clean up shipwrecks. What’s more, there isn’t yet a clear way for one country to non-consensually clean up another’s space debris. “If I, from the U.S., want to put myself in an orbit and there’s a piece of Russian junk there, I can’t just remove the Russian junk,” says Jah. “Russia is the sovereign owner of that piece of garbage. It could constitute an act of conflict.”

It’s these exact kinds of thorny challenges, and the opportunities to work on them, that make space law so compelling to the legal professionals who practice it. There’s another benefit, too: the challenge of exploring new legal frontiers, like astronauts stepping into the unknown.

“A lot of this is just untested law,” says Motiwala. “Who’s going to be that trailblazer that fights that legal battle?”