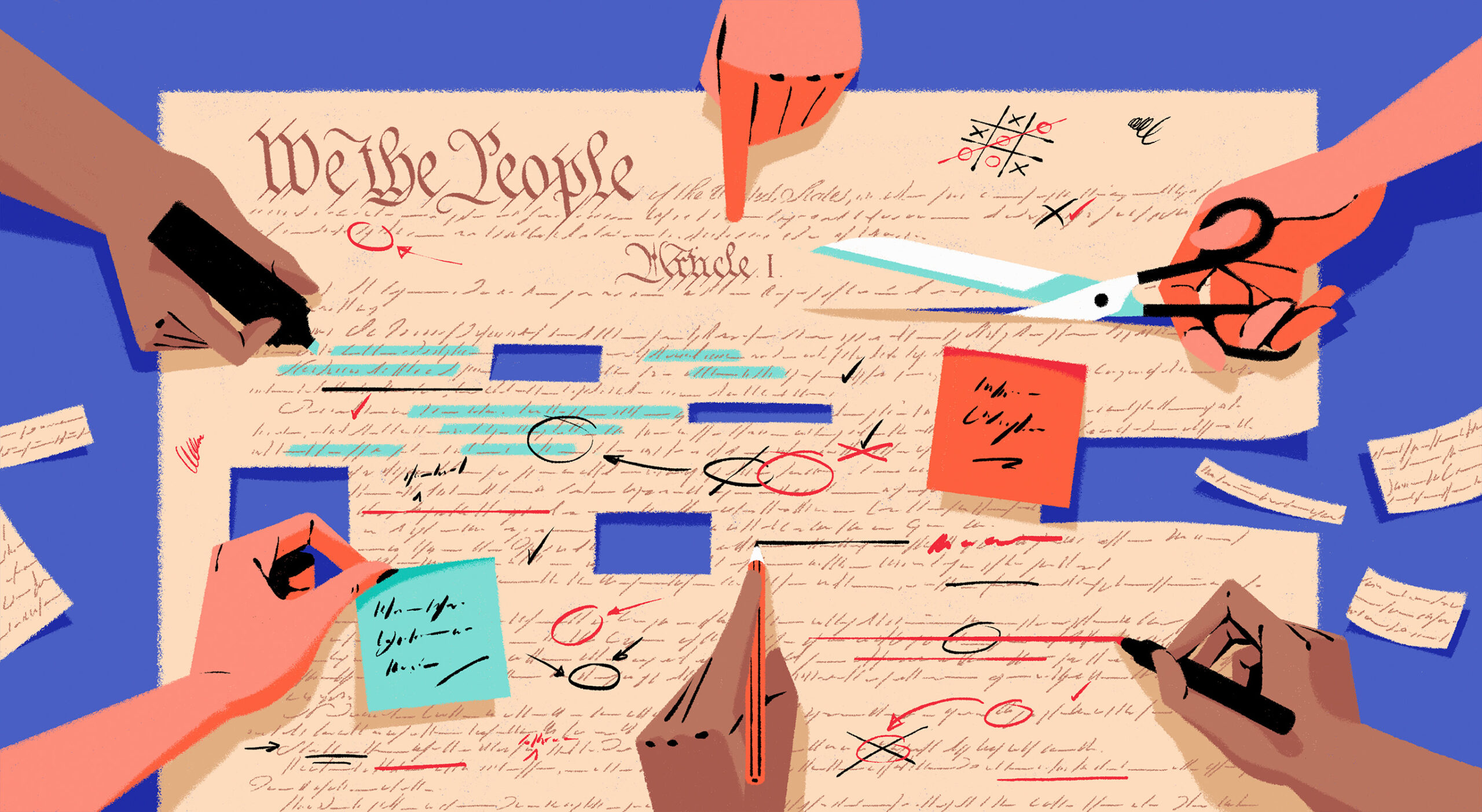

How ‘We the People’ can rescue America.

Written by Professor Sanford V. Levinson

Art by Matt Harrison / Ikon Images

Is it time for America to hold a national constitutional convention? When I suggested the idea of a new convention in my 2006 book, Our Undemocratic Constitution: Where the Constitution Goes Wrong (and How We the People Can Correct It), the response was somewhat tepid. Few people really took issue with me about the undemocratic features of the Constitution. But most at the time, it seemed, were satisfied enough with the policies of national government and didn’t really care about how they were produced.

That was then. Times have changed, and it is obvious that most people, across the political spectrum, have deep reservations about the ability of the national government, especially, to meet the challenges of governance.

Though certainly not the only cause of our present discontent, the U.S. Constitution plays an important role in making it hard, if not impossible, to envision our national government regaining widespread public approval and confidence. Polling indicates a stunning lack of approval – or “confidence” – in our basic institutions. Even the Supreme Court, which usually scores highest in such polls, is now below 50%. This surely doesn’t augur well for our collective future.

In 2017 my wife, Cynthia Levinson – a prize-winning author of non-fiction books for children and young adults – and I published the first edition of Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, their Fights, and the Flaws that Affect Us Today. (A third edition will be published in 2025.) As the title suggests, the Constitution, like the natural world, contains a number of “fault lines” that we Americans generally ignore.

When geological fault lines collide, they can cause catastrophic earthquakes or tsunamis. The same is true of constitutions and their often-ignored structural provisions. We identified 20 such fault lines, some of them quite well known, such as the much-criticized Electoral College, which is quite capable of overturning the popular vote in presidential elections.

We do no honor to what is most admirable about the founding generation if we treat their work as perfect.

Professor Sanford V. Levinson

Similarly well-considered is the indefensible malapportionment of the United States Senate that works against majority rule. Consider that Vermont, with approximately 650,000 people, has the same say in the Senate as the roughly 30 million people of Texas. California, the state with the highest resident population of nearly 40 million, has almost 70 times the population of Wyoming with its .58 million, but the two states share the same number of senators. James Madison was correct in 1788 when he referred to this feature of the Senate as an “evil.” He ultimately argued that it was a “lesser evil” to having no Constitution at all, had Delaware and other small states carried out their threat to leave the Convention. Similar arguments, of course, were made about the necessity to compromise with slavery.

Far more obscure, though of potentially vast importance, is what might happen if a terrorist attack – or a natural disaster or a pandemic – killed or disabled most governmental officials. The U.S. Constitution requires that all members of the House of Representatives be elected.

Abstractly, this may seem like an excellent idea. “Representatives” of the people should be elected, shouldn’t they? But what if, on September 11, 2001, the terrorists controlling Flight 93 had not been stymied by courageous passengers and instead been allowed to reach its probable target of the United States Capitol and had killed (or disabled) literally hundreds of members of Congress? It is altogether likely that we would have had a non-functioning Congress and a consequent presidential (or military) dictatorship.

Dead senators would not be such a problem. They could be replaced, in most states, by governors, as allowed by the Seventeenth Amendment. That solution would be impossible with members of the House, however. We might have to wait literally months before new representatives could be elected and take their seats.

Although a one-time joint committee led by Washington notables suggested a new constitutional amendment to provide for “continuity in government,” – a proposal for which Texas Senator John Cornyn was one of the exceedingly few members of Congress to take seriously – the proposal has gone nowhere in what is now over two decades. The problem remains as an ominous potential fault line.

So, can anything really be done to alleviate the fault lines? Or must we simply pray that there are no future earthquakes or tsunamis?

My own view, which, alas, is becoming stronger and stronger, is that the current Constitution of the United States is, in its own way, a clear and present danger to our national survival. And, because of the sheer importance of the United States in the world, that makes it effectively a threat to world survival. For me, this suggests the desirability – even the necessity – of a new constitutional convention, as the Constitution itself allows via Article V, the amendment provision.

Cynthia, however, like most of my friends and professional colleagues, is basically horrified at the possibility. Interestingly, she – again like most of my friends and professional colleagues – does not disagree with the basic diagnosis that the Constitution has many flaws that require correction. She argues persuasively that a new convention might only exacerbate our divisions rather than contribute to their solution. Why might that well be true?

Article V, which provides for the possibility of a new convention, offers no clue as to how such a convention would be organized. Who would choose the delegates, and what would the voting rules be? Cynthia accurately suggests that we would be at each other’s throats debating these questions before ever turning to the substantive issues that might have triggered the need for a convention in the first place.

Additionally, many Americans are almost thoughtlessly proud of the fact that the Constitution has been formally amended only 27 times since 1787, or, more tellingly, only 17 times since the addition of the first 10 amendments as a group in 1791. But Americans are quite amenable to and capable of considering and voting on constitutional changes. State constitutionalism features not only literally hundreds more amendments, but our collective 50 states have held more than 225 constitutional conventions, at least some of which have led to the replacement of what are correctly viewed as outdated documents with new ones better suited to the times.

A national constitutional convention wouldn’t mean scrapping what may well be admirable in the existing document. But it does mean honoring the hopes of the Founders, expressed frequently in their writings, that we should learn “the lessons of experience,” as both Hamilton and Madison wrote in The Federalist.

They themselves, after all, had audaciously junked what Hamilton called the “imbecilic” system of government established by the country’s first constitution, the Articles of Confederation, replacing the document ratified in 1781 with the brand-new Constitution of 1787. We do no honor to what is most admirable about the Framing Generation if we treat their work as perfect, to be worshipped rather than subjected to what Hamilton in Federalist 1 called an inspiring process of “reflection and choice.”

As Americans we need to resurrect such “reflection” and to believe that “We the People” can actually exercise some “choice” in the matter.

Professor Sanford V. Levinson is a nationally recognized expert on constitutional law, international law, and legal history. He holds the W. St. John Garwood and W. St. John Garwood Jr. Centennial Chair in Law.