How one law school cuts through the rankings noise to focus on better measures of success.

Written by Christopher Roberts

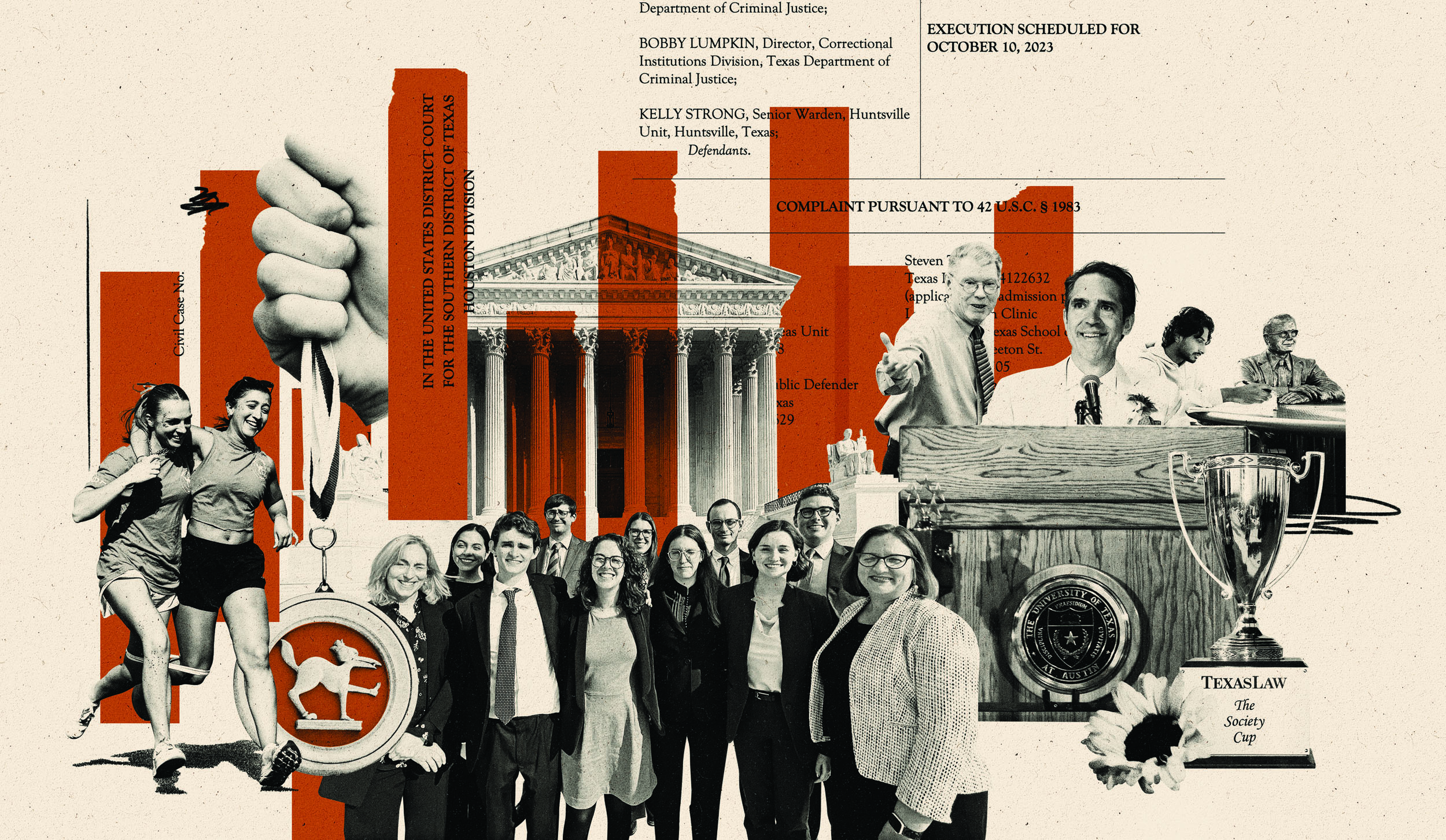

Art by Klawe Rzeczy

In 1906 a psychology professor at the University of Pennsylvania named James McKeen Cattell published American Men of Science, a compendium of biographical sketches of thousands of scientists (including two women, despite the title), assessing their productivity, quality of research, and home institution. The more scientists in Cattell’s book a school could claim, the better the school was by his analysis.

It was the first effort to rank higher education institutions.

Cattell was a complicated fellow. A longtime editor of Science magazine, he was the first psychology professor in the United States and is credited with being an early force in turning it into an accepted field in American academia. He was also obsessive about intelligence, devising ways to allegedly measure it, an all-consuming pursuit that informed his desire to rate other scientists and the places where they taught. (Most accounts say that Cattell was, like many of his contemporaries in the discipline, a eugenicist with disturbing views on genetics that we rightly dismiss today.)

His true legacy, however, is the idea that colleges and universities can and should be judged and ranked.

That task was taken up in 1924 by the president of Miami University in Ohio, Raymond Hughes, who produced A Study of Graduate Schools of America, in which he surveyed academics reviewing themselves and their peers. A decade later, the American Council on Education released their own evaluation of graduate programs, asserting a methodology based exclusively on faculty reputation. Various groups had their own methods of measuring schools and scholars throughout the postwar era, refining not what was measured—faculty reputation—so much as how it was measured, namely through increasingly sophisticated and lengthy surveys.

And then came U.S. News & World Report.

A Whole New Ballgame

In 1983, the Washington, D.C.-based weekly news magazine, in competition for readers with Time and Newsweek, waded into the college marketplace by creating a consumer-friendly guide for high school students and their parents. If the early-20th-century rankings were the result of smart people deciding who was smartest, U.S. News found a way to monetize that pursuit.

Their initial methodology was simple—U.S. News just asked college presidents to name the “best” institutions, rather than surveying all academics or adding other variables into the mix. The premise that reputation was the best indicator of quality persisted.

The publication was a smashing success. Providing an accessible listing of schools, compiled through an easy-to-understand formula and aimed at consumers rather than academics, U.S. News unleashed a tsunami of interest. As the first American publisher to enter the rankings space, they established themselves as the dominant player in what is now a multibillion-dollar industry.

By 1987, the U.S. News rankings were so successful that they published a standalone issue. That same year, the publication expanded their rankings to include graduate and professional schools. The law school ranking, based again on reputational assessments from a small group, included just 20 schools. Harvard and Yale were tied for #1, while Texas Law was #11, sandwiched by the University of Pennsylvania and Duke.

Success—and the ad revenue that went with it—soon spurred innovation. To keep the rankings fresh, and to try to live up to their insistence that the rankings were simply a Consumer Reports-style effort to capture the quality and competitive advantages of different schools, U.S. News decided to expand their rankings formula into a numbers game.

A great law school is about the people and programs as much as the classroom experience. Rankings still have found no way to measure that.

Moving Beyond Reputation

The magazine’s revised approach for law schools, much like with universities, combined reputational surveys with a host of new data-focused metrics. Some, like the LSAT and GPA credentials of the entering class, could be described as measures of eliteness, much like the incumbent surveys. Others, such as bar passage rates and employment percentages, focused on baseline consumer-protection considerations. And still others, particularly a nebulous measure known as “expenditure per student,” seemed to many to be inexplicable on either ground.

The exact formula evolves. Most recently, U.S. News sharply downgraded the weight of all the “eliteness” measures in favor of a dominant role for the formula’s consumer-protection variables. One constant, though, is the hold the rankings have on the minds of law school applicants, alumni, and employers—and hence administrators.

Goodhart’s Law

Not surprisingly, schools have responded to these incentives by looking to maximize their rankings. That was a tall order when the rankings depended solely on reputation, which rarely changed from year to year. Schools could only experiment with long-term strategies, especially involving recruitment of prestigious faculty.

When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

Charles Goodhart

The emergence of data-based objective measures opened different possibilities. Schools could attempt to goose their ranking—and displace higher-ranked schools—on a yearly basis through more controllable strategies, such as admitting fewer students, thereby raising LSAT and GPA credentials.

Unintended consequences of keeping score are the subject of Goodhart’s Law, the principle articulated by British economist Charles Goodhart, who observed that, “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Though Goodhart was writing about monetary policy, the principle explains how people alter behavior to optimize for a metric, rather than for the underlying goal the metric is supposed to represent.

Such behavior isn’t always bad. Being compelled to account for bar passage rates, for example, has spurred law schools to do a better job preparing graduates for the exam.

Still, it’s easy to see how quickly an institution might lose sight of what’s truly important amidst rankings pressures. It’s a fundamental challenge of ranking schools of any kind, and of higher education leaders in guiding their institutional strategic engagement with the rankings process.

With the perils of Goodhart’s Law in mind, what’s a school to do?

What Really Matters

On a given day, if you ask Dean Bobby Chesney if he’s thinking about the law school’s ranking, he’ll give you his honest answer: No.

It’s not that he doesn’t care. “Of course, I want Texas Law to have a ranking that reflects how amazing it is,” says Chesney. And the school’s ranking has risen of late, reaching #14 out of nearly 200 law schools in 2025.

But no one should be captivated by the rankings in the first place.

Dean Bobby Chesney

“But no one should be captivated by the rankings in the first place,” Chesney continues. “The things that matter most aren’t even part of the methodology. The quality of the jobs graduates get? Not part of it. Clerkships? Not part of it. Loan repayment assistance? Culture? Alumni engagement? Cost of attendance and total debt at graduation? None of it matters in the formula,” Chesney added. “Yet these are the very things I’d advise an applicant to value.”

As dean of a top national program that makes a claim to be the best of all the public law schools, Chesney acknowledges that Texas Law is in an enviable position, making it easier to criticize rankings. For schools that struggle to get their graduates past the bar exam or into their first job, the consumer-protection focus on the rankings makes more sense.

Still, Chesney wishes people would pay at least as much attention to the measures of success he says truly matter: “World-class outcomes for our students, unsurpassed return on investment no matter their career direction, and the lifelong relationships they’ll form while here.”

Not Any Jobs—The Best Jobs

Rankings measure the quantity of job outcomes, not quality or desirability. A successful outcome is one tailored to an individual graduate’s needs and wishes, and not a one-size-fits-all-cookie-cutter approach designed to produce one kind of lawyer, in one kind of role. Texas Law is thriving in both quantity and quality.

Texas Law recently reported the Class of 2024 employment number: 98% total employment, a school record. Some of the specifics are particularly eye-popping. For graduates who go into private practice, which nears two-thirds of the class, their median starting salary is $225,000 a year. Only a small number of law schools can make such a claim. “Texas Law graduates aren’t just getting any jobs in the private sector; they’re getting the jobs that are most desired and difficult to get,” notes Angélica Salinas Evans ’95, the school’s dean for career services.

In the same vein, more than 15% of recent graduates have secured one of the most sought-after judicial clerkships in the country, including 50 federal clerkships. That ranks Texas Law #7 in the country for federal placements, alongside UVA, Michigan, and Stanford, and ahead of Harvard and Duke. The school has had clerks on the U.S. Supreme Court for the two of the last three terms, one each for Justices Sotomayor and Thomas.

Finally, the school’s public service career outcomes stand out among peers in part because Texas Law offers the most robust postgraduate fellowship program in the state and one of the most generous Loan Repayment Forgiveness Programs in the country. The ability of the school to thrive simultaneously in all three true outcomes for law careers—private law, public service and public interest, and clerkships—“speaks volumes about the school’s commitment to prioritizing student success,” says Salinas Evans.

Return On Investment

Those accomplishments are impressive, and more so when one considers the cost. Regardless of their ultimate career path, and even with a sizable number of graduates pursuing highly attractive but less remunerative public interest and public service positions, Texas Law graduates enjoy one of the best salary-to-debt ratios of any law school in the country, about 1.8-to-1.

That’s due to tuition rates that remain far below the school’s national competitors. Columbia and Cornell both charge north of $80,000 a year, while Yale, Chicago, NYU, and Penn are all north of $75,000. Of course, those are private schools. What about other public flagships? UVA is $74,000, Michigan is $73,000, and the resident tuition for the top UC schools are $61,000 and $63,000 for UCLA and Berkeley, respectively.

In contrast: Texas Law’s in-state tuition this school year is $38,000, less than half of Columbia and Cornell. The school’s non-resident tuition is just under $57,000, which is still $6,000 less than the in-state tuition at the other public flagships.

With such strong job placement and return on investment, Texas Law has a strong claim to be the best public law school in America, and perhaps—even if only on this measure—simply the best law school, public or private. The rankings don’t account for any of this, but an increasing numbers of applicants seem be taking note.

Relationships

Law school is a financial investment in education, but it’s also a window of time in which long-term relationships and aspirations are forged. And rankings are a blunt tool that is most ill-attuned to valuing the intangibles that boost quality of life both in law school and after—things such as mentorship, alumni connections, extracurriculars, and livability.

Austin is known as a great place to live. But it’s also increasingly expensive. One of Chesney’s most ambitious initiatives is the construction of an across-the-street residence hall for law students with below-market rents. The project will bring hundreds of students into closer proximity to each other and the school, creating endless opportunities for students to better connect with each other.

“Reducing the cost of coming here, while expanding opportunities, animates every decision,” says Chesney.

Texas law enjoys success at scale, with its society program, award-winning professors, top-tier clinics, and boundless professional opportunities for students.

Excellence At Scale

One of the extraordinary things about Texas Law—and another thing that no rankings system captures adequately—is the scale of the school’s excellence. Texas Law’s graduating class usually is more than double (if not three times) the size of other Texas law schools, producing more lawyers in Texas every year by a very large margin. (The number was 412 in 2024, compared to, for example, 213 for Baylor, 140 for Texas A&M, and 190 for SMU, to name three other Texas law schools.) And, yes, a supermajority of them are Texas residents to begin with.

It could be different, of course, if the school simply wished to push its ranking higher. “Imagine if we only enrolled 150 students in our incoming class that had the highest LSATs,” says Mathiew Le, the school’s dean for admissions and financial aid. “Our median this year wouldn’t just be 172,” he notes. “It would likely be much higher and would certainly position the law school favorably for a rise in our ranking—but that’s not our core goal.” And for context he adds, “Yale’s median in 2024 was 174 with 204 students.”

Ideally, rankings would recognize excellence at scale rather than punishing it. As things stand, Texas Law isn’t rewarded for offering great outcomes to two or three times as many students as other schools.

While the hubbub over rankings creates noise, Chesney stays focused on signal.

“My predecessor liked to say that Texas Law is the best place in the world to be a law student,” reflects Chesney. “When I became dean, people asked me if we should say something new. Heck no! That truth—it’s not just a slogan—is based on the things that we know matter most.”