On Tuesday, February 26, 1946, Heman Marion Sweatt went to The University of Texas at Austin’s Office of the Registrar, seeking admission to the School of Law. Sweatt, a native of Houston’s Third Ward, had been a standout student at Wiley College, the historically Black, private college in Marshall, Texas, earning his bachelor’s degree. He had also completed a year of postgraduate study at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, earning strong grades and letters of recommendation from the faculty.

In all ways that would seem to matter, Sweatt was a qualified and eager candidate.

Sweatt was nonetheless denied his admission by the University president of the time, Theophilus Painter, who in turn took his guidance from Texas Attorney General Grover Sellers, who advised that the state’s segregation laws forbid Sweatt’s attendance at UT.

It was an outcome Sweatt anticipated. He wanted to attend law school but knew the current laws, however unjust, were against him and that the University would have little choice but to bow to the attorney general’s directive. But Sweatt would not be deterred.

Establishing a Legacy

With the support of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and Thurgood Marshall as his attorney, Sweatt sued UT. After four years working through state and circuit courts, Sweatt’s case was heard in the U.S. Supreme Court on April 4, 1950. He and Marshall prevailed in a unanimous decision. On June 5, 1950, with a stroke of Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson’s pen, UT—and by extension, all public universities in the country that had not already done so—were compelled to desegregate.

The true moment of UT’s desegregation, however, did not come until September 19, 1950.

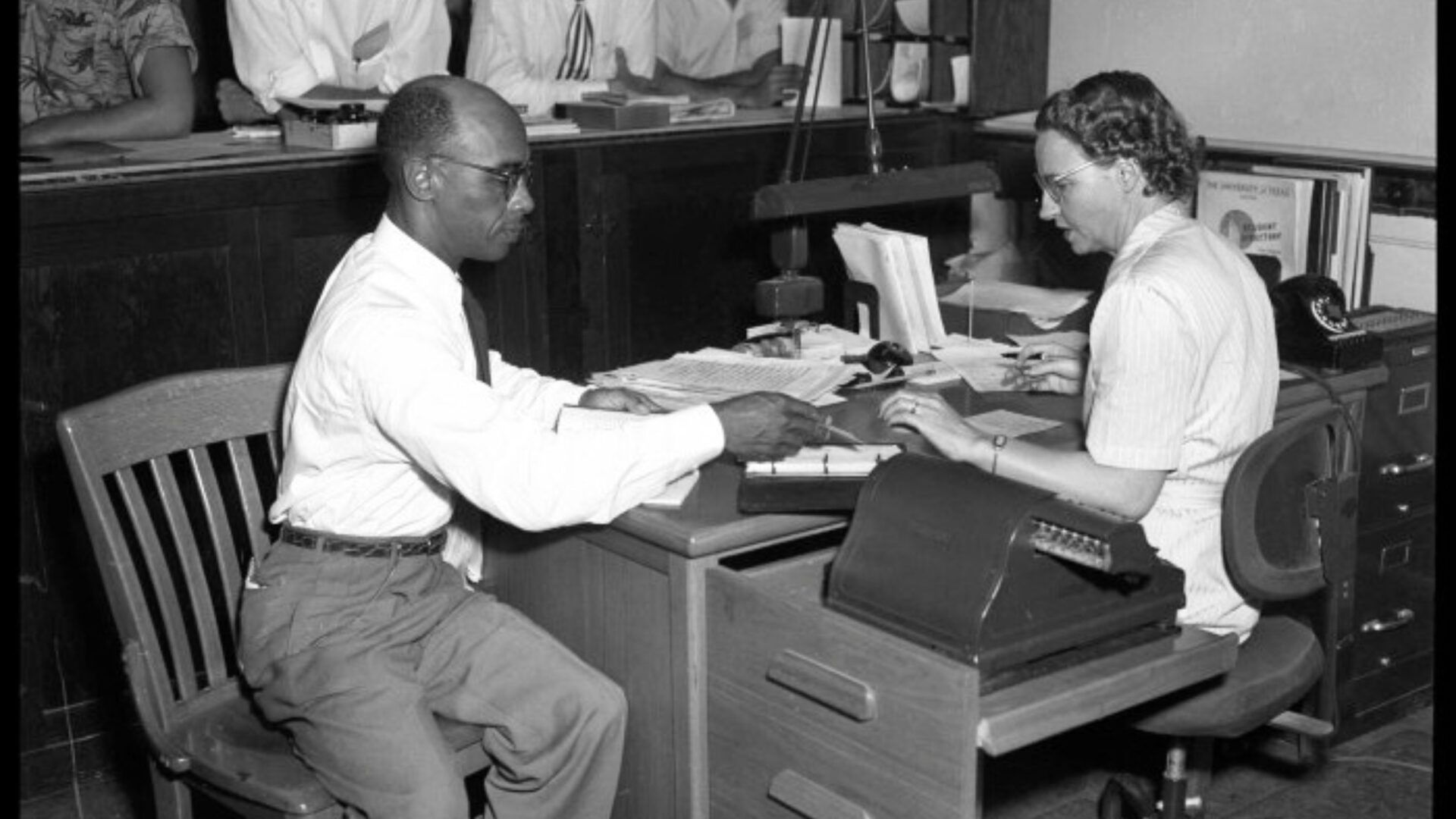

On that day, Sweatt returned to campus with the other incoming law students to register for classes. Sweatt was accompanied by Neal Douglass, an Austin photographer working for Life magazine, to document the unfolding history. Douglass’ photographs, originals of which reside in the University’s Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, captured the moment of Sweatt’s registration and, later, his class attendance.

That day, and all its preceding events, transformed UT, the School of Law, and education in America. Sweatt’s Supreme Court case was a building block of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which stated that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

Portrait Unveiled

The School of Law first formally honored Sweatt and his family in a 2018 ceremony, unveiling an oil portrait of Sweatt that had been commissioned by the Law School faculty. The painting was then hung in the Susman Godfrey Atrium alongside an historical display also featuring a reproduction of Marshall’s letter written to Sweatt after their court victory, encouraging Sweatt to get started on his law school career: “I would suggest that you get in touch Dean Page Keeton of the law school. Dean Keeton is a very decent person… I am sure you will have no trouble with him.”

As part of that portrait unveiling, then-Dean Ward Farnsworth, who had conceived the idea of creating a tribute to Sweatt, explained the decision to put the portrait “in the very center of our school, so that all who pass through here may have a chance to reflect on (his) vast but often too little understood influence on who we are today.”

“The story of Heman Sweatt is ultimately that one man—armed with friends and family and a good lawyer—truly can change the world,” Farnsworth added.

75th Anniversary Ceremony

On Sept. 12, the Law School is partnering with The Precursors, a campus group that keeps the memory and celebrates the achievements of UT’s first generations of Black students, to mark the 75th anniversary of Sweatt’s enrollment in Texas Law and the University’s integration.

Speakers will include UT President Jim Davis, Texas Law Dean Bobby Chesney, Precursors President Cloteal Haynes, and Arleas Upton Kea ’82, the current president of the Texas Exes and the Law School Alumni Association’s Outstanding Alumna award winner for 2024. Gary Bledsoe, Class of 1976 permanent class president and Texas NAACP president, will also appear.

Recognizing Sweatt’s arduous battle for equality—never backing down in spite of tremendous personal cost—will allow members of the Law School and University communities to reflect on how much is owed to the civil rights pioneer.

“Every schoolchild in America, and even in much of the world, knows the names of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and John Lewis,” says the Law School’s director of communications, Christopher Roberts. “I hope people will also know Heman Sweatt and speak of his courage and commitment, recognizing what he did for opportunity in higher education in our country.”

The invitation-only ceremony honoring Sweatt takes place on Friday, September 12, at 12:30 p.m. in Texas Law’s Atrium, near Sweatt’s portrait and historical display.

To learn more about Heman Sweatt and Sweatt v. Painter, one can visit the Tarlton Law Library’s digital collections, or the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History’s Heman Sweatt Symposium on Civil Rights collection.

The film “Admissions on Trial: Seven Decades of Race and Higher Education,” by documentarian Lynn Boswell ’93 covers the Sweatt v. Painter case in depth.

The definitive book about Heman Sweatt the man, as well as the plaintiff, is Gary Lavergne’s “Before Brown: Heman Marion Sweatt, Thurgood Marshall and the Long Road To Justice.” Lavergne, who retired in 2020 from his role as UT’s director of admissions research and policy analysis, was another featured speaker at the Law School’s 2018 tribute to Sweatt.