When Andrea Meza ’15 sees a chance to help people, she takes it.

That’s why, when mass firings of federal workers early this year led to a bevy of legal actions, she quickly launched a pro bono initiative within her organization, the nonpartisan, public interest Government Accountability Project, to expand the group’s capacity to support whistleblowers, hoping their information could provide crucial guidance in a moment of legal uncertainty.

Meza says her ability to take that kind of responsive action—one that’s sophisticated, strategic, and rapid—owes something to the skills she developed as a member of the Chicano/Hispanic/Latino Law Students’ Association at Texas Law.

“CHLLSA is a microcosm for practicing so many things that are transferable to success in the legal profession,” says Meza, “like how to manage budgets, meet deadlines, resolve conflict, and advocate for yourself and for organizational goals.” For Meza, who is the Director of Advocacy Campaigns as well as Director of the Immigration and Food Integrity Campaigns at the Washington, D.C.-based Government Accountability Project, as for so many of CHLLSA’s more than 1,000 alumni, the organization has left a lasting mark. The skills she sharpened there guide her daily work, while CHLLSA remains a vital resource for current Texas Law students as they build successful careers in the law.

Founded by Law School students in the fall of 1969, the organization has guided generations of aspiring attorneys, providing mentorship, leadership, and networking opportunities, while supporting the broader community through pro bono opportunities and outreach to youth considering law careers. CHLLSA has built a pipeline of future leaders in the legal profession and strengthened representation within the justice system.

Inspired by Chavez and Huerta

CHLLSA’s origins harken back to the late 1960s, emerging amid a nationwide surge of Mexican American pride and activism.

When Senior U. S. District Judge David Briones ’71 enrolled at Texas Law, the nation was roiled by widespread social unrest, from anti-Vietnam War protests to civil rights activism to the burgeoning labor rights movement. In California, Cesar Chavez and Delores Huerta’s National Farm Workers Association had successfully organized a series of strikes among farmworkers, seeking fair pay, safer working conditions, protection from harmful pesticides, and the right to organize.

Mexican American students at colleges and universities, mostly in California and Florida, were forming alliances with labor organizers and seeking ways to apply lessons learned from Chavez, Huerta, and others to the inequality they faced on their campuses.

In October of 1969, Briones, an El Paso native, along with several other Texas Law students from the Rio Grande Valley and San Antonio, flew to northern California to attend meetings being held by students at the University of California, Berkeley and other California schools who were organizing for representation in state university administrations, as well as for improved pay and benefits for student workers throughout the UC campuses.

(Briones recalls that his trip was only made possible by the generosity of Southwest Airlines founder Herb Kelleher, who gifted the Texas Law students free roundtrip flights to attend the meetings.)

Once back in Texas, Briones, along with classmates Edward Prado ’72, Federico Pena ’72—who became Denver’s 41st mayor and then-President Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Transportation—and nearly two dozen other interested students, decided Texas Law needed its own group for students of Mexican American heritage.

“Most of us were first-generation, and we went to law school with the thought that we’d use our law degrees to fight social injustices we’d seen growing up and that were in the news,” Prado says.

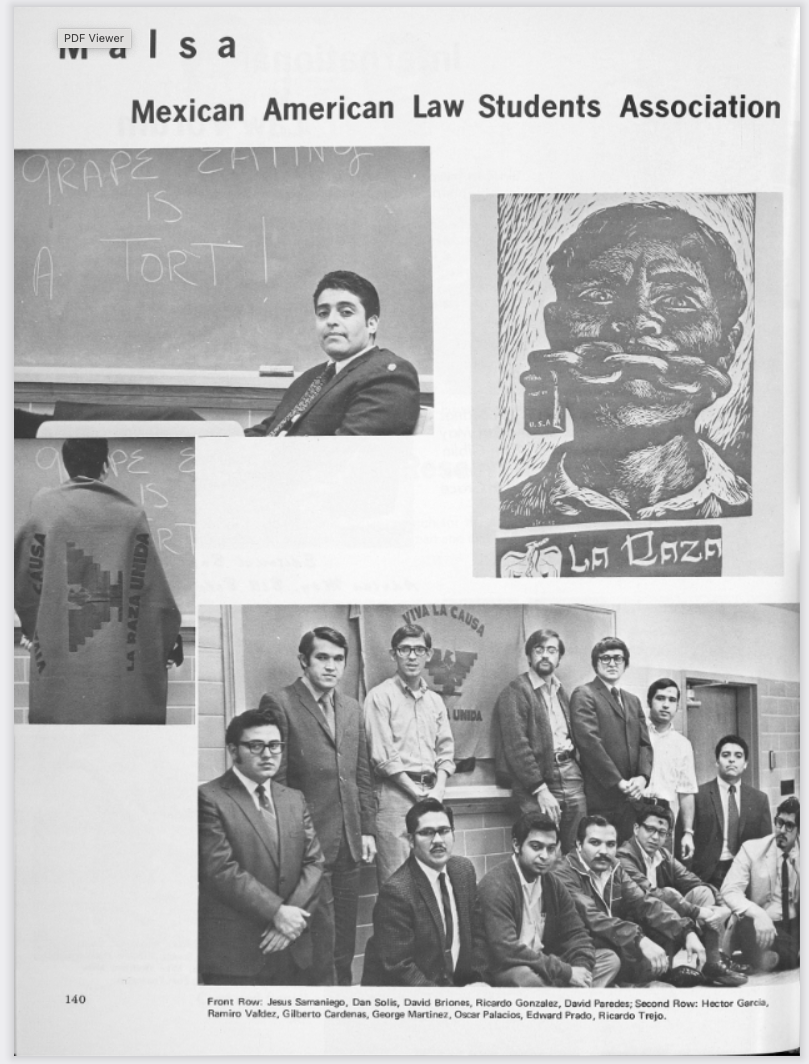

The students’ first order of business was choosing a name. Some wanted to use the term “Chicano,” in the spirit of a nationwide trend of reclaiming a word that had been commonly used as a derogatory epithet. Others found the word threatening, or worried that university law school administrators would take it that way. In the end, the name “Mexican American Law Students Association,” or MALSA, won out.

In MALSA’s early days, its members formed study groups and volunteered together at Legal Aid. Prado recalls joining a boycott at a gas station on “the Drag” across from campus that refused service to a Black student. MALSA filed a formal complaint with the University against a fraternity whose inebriated members wore sombreros and serapes on Cinco de Mayo. In May 1970, when the Ohio National Guard opened fire on unarmed students at Kent State University protesting the Vietnam War, killing four and wounding nine, MALSA joined a class boycott and marched in Austin alongside thousands of students from across The University of Texas at Austin.

We helped each other and encouraged those having a hard time to stick it out.

Edward Prado ’72

But more than anything, MALSA provided much needed daily support for its members. “None of us had a background in law,” says Prado, whose parents dropped out of eighth grade. “It was an uphill battle for many. We helped each other and encouraged those having a hard time to stick it out.”

The support Prado received from MALSA helped propel him onto a career path that included serving for nearly 35 years as a U.S. judge, including as an appellate judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, and 19 years as a district judge for the Western District of Texas. Prado was the U.S. ambassador to Argentina from 2018 to 2021. Today, he’s of-counsel at Bracewell’s San Antonio office, where he mentors young attorneys.

Lifeline for Students

In its early days, name changes were frequent. In 1972, MALSA evolved into La Raza Law Student Association. The following year, those in favor of using Chicano won out, and the group became the Chicano Law Student Association, or CLSA. But whatever its name, the mission stayed the same.

For Judge Hilda Tagle Knebel ’77, the first Hispanic woman to become a federal judge in Texas, the group was a formative part of her Texas Law experience. “CLSA was my lifeline,” she says.

As one of three Hispanic students in her freshman law class of 150, Tagle Knebel spent countless hours studying, commiserating over coursework, and socializing in Room 109 where CLSA—which soon became ChLSA—operated an office alongside the Thurgood Marshall Legal Society and the Women’s Law Caucus.

Roberto Soto, ChLSA president in 1976, recalled a strong sense of solidarity among students in all those groups at the time. Most students with Latino heritage were active in ChLSA, he said in a 2005 “CHLSA Today” newsletter, and they often studied together. ChLSA and TMLS worked closely, too, as a unified community, with members joining one another’s events.

“Room 109 was a watering hole for people of similar backgrounds,” says Tagle Knebel, who credits the support she found through ChLSA with her professional success. Her classmate and fellow CLSA member Doug Chaves ’77 encouraged her to stay in law school when she felt overwhelmed and considered dropping out. “We were there to back each other up,” she says.

Spirit of Giving Back

In the early 1980s, ChLSA began hosting an annual cultural celebration and awards banquet. Over the years, the event’s keynote speakers have included luminaries such as Huerta, whose movement indirectly led to the group’s founding, and the groundbreaking publisher of Hispanic Magazine, Alfredo Estrada.

Mario Barrera ’84, a labor and employment partner in Norton Rose Fulbright’s San Antonio office, fondly recalls early days of ChLSA’s now annual, widely-attended “fajita fest” fundraiser, where he and fellow students would work the grills and introduce classmates to a $1.50 plate of fajitas, beans, and rice, a dish that at the time was still unfamiliar to many.

Barrera’s arrival at Texas Law in 1981 at age 22 marked his inaugural journey out of the Rio Grande Valley. “Being in Austin for the very first time was overwhelming,” he says. In law school, he says, “I felt like I was miles behind a lot of people who’d been in incredibly competitive undergraduate programs.”

During the first few difficult weeks, Barrera connected with 2L and 3L ChLSA members during get-togethers at local students’ homes over informal meals. “There were these wonderful people who were willing to share,” says Barrera, who picked up study habits from his fellow members. “ChLSA was my security blanket. It was what I needed to recharge my battery.”

As a 2L and 3L, Barrera became a mentor to ChLSA 1Ls. The spirit of paying it forward he learned from—and then fostered through—the group has carried through his 30-plus-year career. Barrera has coached Texas Law moot court teams, served on Texas Law Dean’s committees, and acted as a member of the Law School alumni association’s executive board.

“The career I’ve had, all of it is due to the UT Law School and to ChLSA, and I’ve never forgotten that” Barrera says.

Another aspect of ChLSA’s legacy, and in the spirt of its founding, involved advocacy to encourage the school’s hiring of more Latino faculty. When Professor Gerald Torres joined UT Law in 1995, many ChLSA alumni were especially gratified. He grew to be a popular and successful professor of administrative, environmental, and federal Indian law, as well as property, among other courses, and Torres remained on the Forty Acres until 2013, when he joined the faculty of Yale Law School.

From Pro Bono Work to Networking

When Meza joined her first group meeting as a 1L in 2012, she was looking for community. The group had changed names once again, to its current iteration, which includes “Latino”: the Chicano/Hispanic/Latino Law Students’ Association.

Meza quickly built relationships with role models in CHLLSA who helped her navigate the selection of courses and law clinics to participate in. She developed leadership and organizational skills through her work on the organization’s fundraising efforts and community events.

As a 2L and CHLLSA’s external vice president, she managed the group’s pro bono work—including assisting with applications for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program—and organized and expanded its Latino Law Day, an ongoing event that gives prospective law students a glimpse of what it’s like to be in law school. Meza secured funding for event giveaways, invited a local bar prep course to teach a bar prep preview, and recruited professors to run a mock 1L class for participants.

“Since then, the event has really taken off,” Meza says. “It’s inspiring to see how today’s students have expanded and grown it even more.”

For 2014, CHLLSA won its bid to host the 18th annual National Latino Law Student Association conference for the first time. It took a tremendous amount of teamwork to create the winning bid. “That’s what I think of when I think about CHLLSA,” says Meza. “Working in partnership to accomplish great things for the community. And that’s very helpful for the practice of law!”

That’s not all Meza took away from her time in the group: she also met her husband, Carlos Carrasco ’14, now an energy regulation attorney at Haynes Boone LLP in Austin, at her first CHLLSA meeting.

An Enduring Legacy

Current CHLLSA President Maria Rodriguez ’25 leads a group that today is nearly 50 members strong. From the first few weeks of her 1L year on, “CHLLSA has felt like a little piece of home away from home,” says Rodriguez, a first-generation student from Grand Prairie, Texas, who has Mexican ancestry.

The group supports members in attending an annual national bar convention, a formative experience where law students get the chance to network with attorneys throughout the U.S.

Last year, CHLLSA helped four students attend the conference; this year, it will support five. CHLLSA’s annual banquet continues as a keystone event for celebrating accomplishments as a group and draws hundreds of attendees from the Law School, CHLLSA alumni, prominent Hispanic judges, and other dignitaries from UT and the legal community.

Other recent CHLLSA events have included a fall boat cruise to bond with peers and a speed networking event. CHLLSA’s Dress for Success scholarship has awarded $500 primarily for 1Ls who need financial assistance to purchase suits or business attire for internships or job interviews. Through panels, lectures, and forums, CHLLSA members also have ample networking opportunities with local attorneys and judges, helping students to vastly expand their network.

Today, CHLLSA members continue to find community meeting in the group’s offices. “CHLLSA is still that safe space for people where you can really lean on each other for support,” Rodriguez says. “It’s an oasis and it’s wonderful to see how much of a through-line it’s been for students to get a start on their legal careers.”

For that, Rodriguez acknowledges, meaningful credit goes to Briones, Prado, Tagle Knebel, Barrera, and Meza, and all those who carried the torch of CHLLSA’s mission throughout more than a half-century of struggle and success.

Background reporting for this story was done by Mauro Ramirez ’07, writing for the Fall 2005 “CHLSA Today” newsletter. The editors are grateful for his efforts, which made this story possible.