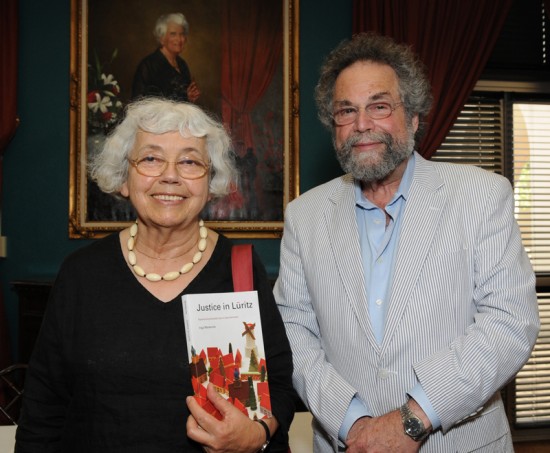

Inga Markovits, “The Friends of Joe Jamail” Regents Chair and Professor of Law, has published her own English translation of her German-language book, Justice in Lüritz: Experiencing Socialist Law in East Germany. The book is an in-depth examination of a mid-sized East German town under socialism, as told through court records and supplemental interviews. Markovits sifted through forty-four years’ worth of documents to produce a comprehensive volume that has been hailed by the Law and Society Association as one of two best works of sociolegal history published in 2010 (she shares the honor with Freedom Bound by Christopher Tomlins of the University of California, Irvine.)

Writer Dale Cannedy recently interviewed Markovits about her book and receiving the J. Willard Hurst Prize. A transcript follows.

Dale Cannedy: Justice in Lüritz focuses on East Germany under socialism. What was your experience of East Germany before its collapse?

Inga Markovits: During my childhood, the Iron Curtain divided Germany, and I didn’t know much beyond the claims that East Germany suffered the evils of socialism. Then I went to university in Berlin. Because I had a West German and not a West Berlin passport, I could cross the border into East Berlin and did so often. Later, as a researcher and legal historian, I traveled frequently to East Germany under socialism, so I came to know the country and its legal system quite well.

I learned quickly that people spoke two languages in East Germany. They spoke their own, private language and the official, political language of the Party—the way people in the 18th century court of Frederick the Great spoke French inside the court and German outside. When speaking their ordinary language, I found East Germans to be extraordinarily communicative and quite open about things.

DC: How did you first discover the legal archive that became the basis of Justice in Lüritz?

IM: I learned from East German colleagues that there were courts who might still have all of their files since the end of the War, because the East German court administration did not have enough personnel to weed things out. So I made a special trip to look around for courts that might have all their files intact. After quite a search, I found one such courthouse.

The problem was that, although they might not have the staff to throw things away properly, most courts didn’t have the space to keep everything. But the courthouse of Lüritz was an old Renaissance building, a three-winged palace. They had a lot of space—not only for their archive, but also for the storage of waste paper. It was there, among the waste paper, that I found thousands of additional files.

DC: How long did you spend with the archive?

IM: It was an incredibly lengthy project. First off, East Germany is far away from Texas, so there was a lot of travel. I got grants from the German Volkswagen Foundation to spend twice a semester there. One of these semesters, my husband taught at Hamburg University and we took our children. I would leave Monday morning for my little town and come back Saturday evening. For years, I also spent a few additional weeks when I could; at Christmas, for instance, or over the summer.

The court decided about a thousand cases a year. I did not have an assistant help me go through files, because it’s really the kind of material you have to read yourself to understand what’s going on. And I could not make copies, because the court had only one Xerox machine.

I can very well understand why there aren’t more books like this…it’s simply too much work. I began in the early nineties and finished the German version of the book in 2006.

DC: How did the court’s archive reflect the social history of East Germany?

IM: I discovered a system that began with fervent belief among the early judges that they were serving and building a better society, and that law would not play a particularly important role in it. It started out with a lot of hope and not much interest or even knowledge of law The first judges were called People’s Judges; they were bricklayers or truck drivers who took crash courses in law and were convinced socialists. But as the hopes for a new and better society waned, the reliance on law increased. You ended up with many disappointments, much political cynicism, and a growing hope for law. In everyday East German life, there was far less injustice than Americans or West Germans would assume. Overall, the system relaxed. You could go to jail for a political joke in the 1950s and 1960s, but you wouldn’t by the ’70s or ’80s.

East Germany was an authoritarian system, with a suspicion of individual rights, but not one with contempt for human beings. They believed in social welfare rather than political rights. People were entitled to a place that was warm, safe, and dry; enough food; education; and free medical care. But the state had no use for free speech and freedom of assembly. The greater evil of the system, I think, lay not in its violations of people’s rights but in its suffocating embrace. In the late 1980s, people just wanted to get away; they just wanted to travel. The building of the Wall had solidified the system, but it also cut off all the fresh air and made people increasingly dissatisfied. Eventually, the system collapsed under its own weight.

DC: What was your reaction to winning a share of the J. Willard Hurst Prize?

IM: I was very honored and, with Christopher Tomlins as co-recipient, felt in very good company. Willard Hurst was really the founding father of the Law and Society movement. He was a very famous social legal historian. I met him once, when I was a beginner, and I was too shy to ask him any questions. But I’m glad I met him—he was really a great man.