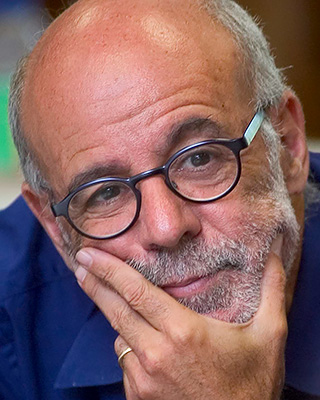

Texas Law Prof. William Forbath, who has been writing about law and the American labor movement for over 25 years, has been a close and engaged observer of the monumental change to the nature of work in America and the resulting plight of American workers. This Labor Day, Prof. Forbath and Temple Law School Prof. Brishen Rogers co-authored an opinion piece for The New York Times suggesting profound changes to labor law in the interest of serving a new generation of labor. We reprint the piece in full below.

Texas Law Prof. William Forbath, who has been writing about law and the American labor movement for over 25 years, has been a close and engaged observer of the monumental change to the nature of work in America and the resulting plight of American workers. This Labor Day, Prof. Forbath and Temple Law School Prof. Brishen Rogers co-authored an opinion piece for The New York Times suggesting profound changes to labor law in the interest of serving a new generation of labor. We reprint the piece in full below.

A New Type of Labor Law for a New Type of Lawyer

by William E. Forbath and Brishen Rogers

September 4, 2017

Labor Day was born in the late 19th century, during a time of raw fear about the path of economic development. Opportunities for decent, middle-class livelihoods seemed to be shrinking, and the “laboring classes” confronted a grim future of what many called wage slavery. Conservatives held most of the seats of power, but reform-minded politicians, activists and policy mavens were thinking big about labor’s rights and wrongs.

Lately, driven by a sense that decent work is becoming a thing of the past, liberals and progressives have been thinking big about these things again: The Democratic congressional leadership has proposed a $15 minimum wage and a huge infrastructure investment, while the Center for American Progress has proposed a New Deal-style federal jobs guarantee. Those are good ideas. But good ideas about economic and social policy aren’t enough.

We can’t hope to build a more equitable economy unless working people have strong organizations of their own. During and after the New Deal, unions were essential to forging a broad new middle class — not only because they raised wages and benefits, but also because they countered corporate and financial political power, which today is the greatest impediment to serious change. Without a rejuvenated labor movement, it’s almost inconceivable that breakthrough reforms will come to pass.

Democratic lawmakers know that their party was founded on the proposition that concentrated wealth seeks to convert its economic power into political power and that left to its own devices, it puts our democracy at risk. A new workers’ movement would also be a bulwark against the old Jeffersonian nightmare of rule by a self-perpetuating economic oligarchy. For both reasons, progressive lawmakers and policy analysts need to promote a new generation of labor organizations.

They can do that by putting labor-law reform at the top of their agenda. The National Labor Relations Act was written in the 1930s, when big factories and large industrial companies dominated our economy; its provisions are a terrible fit for today’s economy in two basic ways.First, because it arose out of the struggles of factory workers with big corporate employers, our labor law encourages bargaining at the employer or work-site level. This made sense when most workers were in large factories. But today’s workplaces are much smaller, even if they are owned or controlled by big corporations. Fast food workers are split among thousands of locations. Janitors labor in small groups, at night, out of the public eye. Warehouse workers in Wal-Mart and Target’s supply chains are often employed by temporary agencies and hired by day or even hour to load trucks. Uber drivers and Amazon delivery drivers work alone.

Second, our labor law holds businesses accountable only to the workers whom they “employ” in an old-fashioned, contractual sense. That too made sense in the industrial era, when leading companies had millions of employees. But today, janitors, Amazon delivery drivers and warehouse workers are often employed by subcontractors who have little real power over their livelihoods. And Uber and Lyft drivers are misclassified as independent contractors. As a result, these workers don’t have clear rights to bargain with the companies that actually set the rules. And these workers are subject to big restrictions on striking or picketing against such “third party” companies.A few simple but bold legal reforms would make a world of difference. First, Congress could pass laws to promote multi-employer bargaining, or even bargaining among all companies in an industry. If all hotel brands, all fast-food brands, all grocers or all local delivery companies bargained together, none would be placed at a competitive disadvantage as a result of unionization, which is often the main reason employers resist it so fiercely. Second, Congress could ensure that organized workers can bargain with the companies that actually profit from their work by expanding the legal definition of employment to cover more categories of workers.

Smart organizers are already working toward just this sort of labor relations model. Fast Food Forward, the group that has been organizing fast-food workers to demand $15 an hour and a union, is one. Rather than going store by store, they have been taking the fight to the streets and to social media, pushing major chains to take responsibility for working conditions both in their own stores and among franchisees. Strengthening bargaining rights as we’ve suggested could make that vision a reality.

As long as that isn’t yet possible at the national level, progressive states like New York and California, or cities like Chicago and Los Angeles, could develop this sort of model within their own jurisdictions. That would require modest progressive reform out of Congress, making national labor protections a floor but not a ceiling, just as it has already done with wage, hour and anti-discrimination laws. But that way, as in the pre-New Deal era, states and even cities could experiment with how to empower new sorts of worker organizations.

Ideas like these cut against the grain of mainstream debate, which assumes that rebuilding the industrial sector is the key to a broad middle-class economy. There is nothing wrong, and much right, with such efforts. Still, the reality is that a great majority of today’s working class is no longer in factories, and will never be again. Organized and united under new labor laws that they had a hand in achieving, retail, hospitality, health care and other service workers could become a solid, multiracial working-class base for a progressive Democratic Party.