As a student at the University of Texas School of Law, Aurora Martinez Jones wanted actual courtroom experience, so she signed up for the Children’s Rights Clinic. She gained much more than she expected.

“I can say with one hundred percent certainty that the clinic changed the entire trajectory of my professional career,” Martinez Jones said. “I interviewed with a lot of large law firms and was not seeing people who looked like me, a woman of color. The families and children in my court cases did look like me. That really had an impact.”

After nearly 8 years in practice, primarily involved in child welfare, Martinez Jones is now an associate Travis County judge dedicated to the child welfare docket. “I can effect greater change as a judge,” she said. “There is so much meaning in the work that I do, and I wouldn’t be here if I hadn’t been in that clinic.”

Judge Jones’ in a Travis County CPS courtroom with the stuffed animals she keeps on hand to help the kids they serve.

Every year, 300,000 children in the US – 20,000 in Texas – are removed from their families and placed in foster care. All of these children need a lawyer to advocate for them and ensure that the judges determining their future hear their perspective as well as that of other parties. But not all get one.

In Texas, when the Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) alleges abuse or neglect by a parent and seeks custody of a child, that child has a right to a lawyer. In Travis County, the district court appoints the Children’s Rights Clinic (CRC) as the attorney ad litem for the child. CRC students sit first chair at hearings, mediations, bench and jury trials, and appeals, supervised by a faculty member.

The CRC provides hands-on experience to future litigators and teaches a variety of skills applicable to the practice of any type of law. The latter is true of clinics in general. “Our clinical courses are designed to bridge the classroom and the practice of law,” said Eden Harrington, associate dean for experiential education. “Students in clinics like the CRC represent some of their first clients under the close supervision of our outstanding clinical faculty, which is a great educational and professional experience.”

Clinic basics

Students apply for one of 16 clinics at the law school in their second or third year. The CRC accepts up to 12 new students each semester. Students attend a weekly class covering child welfare policy, substantive family law, trial procedure, and legal ethics, and meet weekly with a supervising attorney.

“We start with a sort of boot camp orientation,” says Leslie Strauch, one of the CRC’s supervising attorneys and a former Travis County assistant district attorney. “We give them a lot of information about how cases start, go through the system, and can potentially end. Then students come to court to observe.” Each student takes on three ongoing cases and three new ones. For those cases, students interact on their own with their clients, other lawyers, DFPS caseworkers, court-appointed guardians, foster parents, teachers, medical and mental health professionals, and police officers. They talk next steps and strategize with their supervising attorney, typically much more often than once a week.

“We talk whenever something comes up – nights, weekends, holidays,” said CRC supervising attorney Lori Duke, who has worked in private practice and as a district court staff attorney. “It’s usually an emergency, such as a kid has run away or a placement has fallen apart.”

CRC director F. Scott McCown, a state district court judge from 1989 to 2002, joined the UT faculty in 2013 and teaches the weekly class. “There’s the law and there’s the practice, and he does a good job of combining both,” Duke said. “We also have class discussions so students can get ideas from each other on practical issues.”

Clinic students receive a temporary bar card so they can appear in court, McCown said. Most appearances involve preliminary or review hearings, but the CRC regularly tries contested matters, including bench trials and jury trials. All students gain some kind of courtroom experience. A second- semester advanced clinic allows students to continue handling cases.

Career path

Law clinics in general help students determine what they want to do as lawyers, said Duke. Many students who take the CRC are interested in litigation. A number become fascinated by child welfare and go into that area of practice, as Martinez Jones did, but most do not.

“You obviously have students in the clinic who are interested in families, children, and CPS work, and closely related things like disability rights and immigration,” Duke said. “But we also have students who plan to go to big firms and do intellectual property work or civil litigation.”

One of those is Sara Block, currently an associate at Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP in her hometown of Chicago. “I was pretty sure I didn’t want to litigate, but wanted to give myself the experience of litigating in a safe space before I totally ruled it out,” said Block. During the clinic, she handled a termination of parental rights case. Afterward, she called her mother, a litigator. “I said, we got the result we wanted and she said something like, you must be so pumped, and I was not. She said, if you don’t love the winning, then it’s not for you.”

The CRC proves valuable regardless of the route students ultimately choose. “You need to get your feet wet practicing what you learn in the classroom,” Strauch said. “Real work experience cannot be replicated anywhere else. It makes students much more confident about the choices they make. Clinics can change students’ minds, whether they want to go one direction or not.”

Courtroom Experience and Practical Skills

Clinical education has grown nationally and at UT over several decades. One of the first two clinics at UT, the CRC was founded in 1980 by John Sampson, now a professor emeritus. “This kind of hands-on learning responds to the desire of students to learn by doing, and the desire of employers to have practice-ready graduates,” said McCown.

“The idea of being responsible for actual clients in cases is a selling point of the CRC,” said Duke. “Some clinics don’t have that opportunity. I would guess my students are in court 10 to 15 times a semester, at least.”

The opportunity to practice courtroom skills attracted Ian Pitman, now a partner at Jorgeson Pittman LLP in Austin. “I wanted to make sure I wasn’t going to be a fish out of water,” he said. “As far as examining witnesses, introducing evidence and that sort of thing, you have to learn by doing. There is also a lot of interaction outside of the courtroom with professionals, other attorneys, and clients. You learn to leverage information to get positive outcomes without going to court.”

In fact, clinic students learn a wide range of practical skills – what Dylan Moench, currently staff attorney at the Supreme Court of Texas Children’s Commission, calls the nuts and bolts of how to practice law.

Some of what clinics teach is process, said Michele Morgan, currently a solo practitioner, including creating a paper trail of the when, where and whom of conversations. “A lot of practical skills you don’t learn in class – billing, how to interview witnesses, how to stay calm when you hear patently ridiculous stuff.” The advanced clinic involves a lot of trial preparation, such as interviewing witnesses and preparing documents. “These are really invaluable skills. There is the way it’s supposed to work on paper and the way it actually works.”

Crystal Leff-Piñon, managing attorney for The Family Helpline, counts time management among the valuable skills learned in the CRC. Participants in the clinic have to juggle their cases – meeting clients, preparation, and going to court – with classes. Clinic students also learn how to work with other attorneys, including the opposition.

“A lot of attorneys we see around the courthouse say, ‘I wish I had taken a clinic, I would have a better idea of what I’m doing’,” said Strauch.

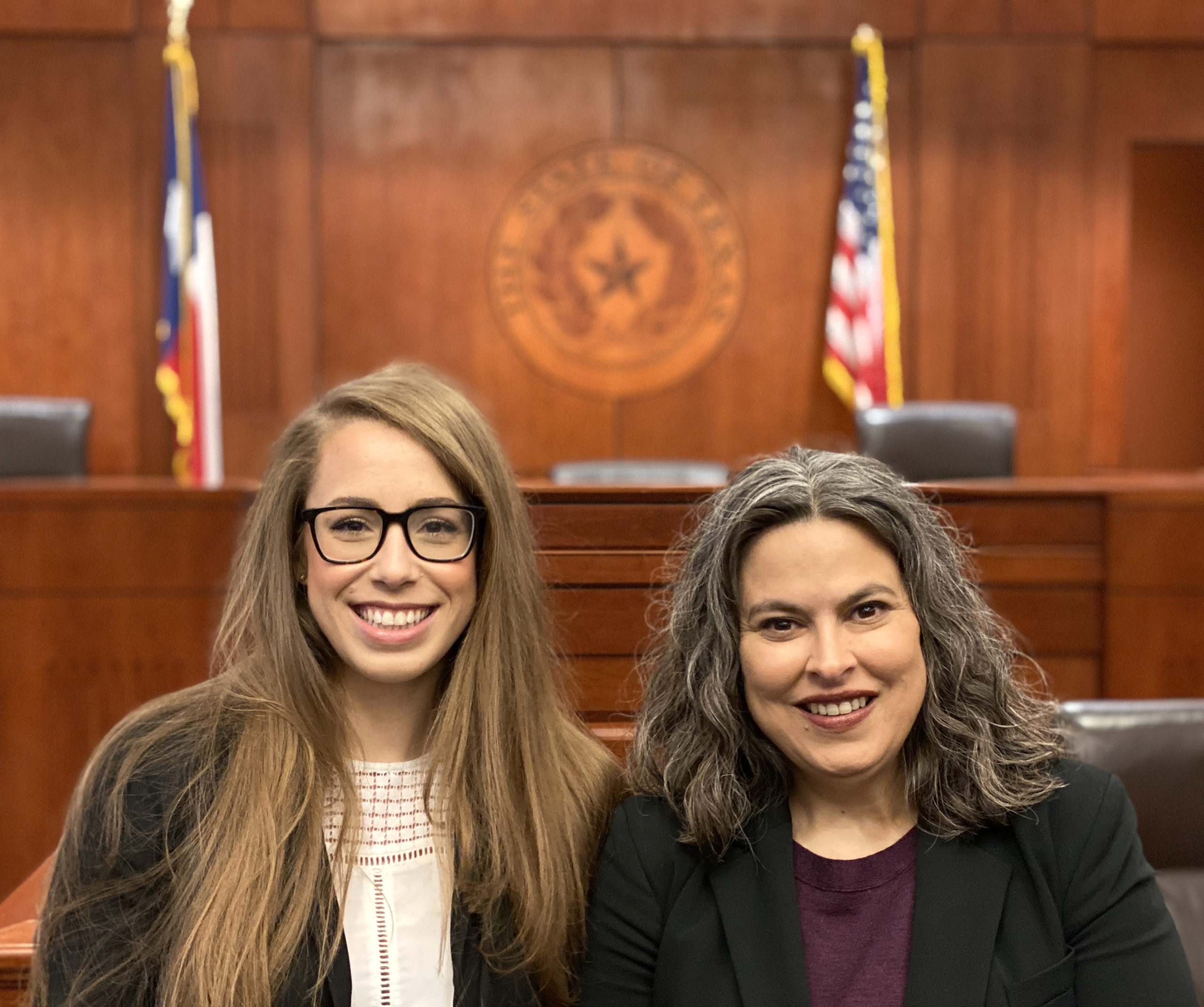

Bethany Copeland ‘20 and supervising attorney Leslie Strauch ‘95 of the Children’s Rights Clinic after having won their bench trial in November of 2019.

Client Relationships and Advocacy

Experience dealing with clients has particular value in the area of children’s rights. “When you’re talking to a 6-year old and they say, ‘I don’t want to live with my sister,’ you have to figure out whether that’s a real thing or they just had a fight about a Barbie,” Morgan said. “You learn to check multiple times and confirm what they are thinking.”

Ian Spechler, now administrative law judge at the Texas State Office of Administrative Hearings, found that gaining his young client’s trust was key. “By the time they are in this situation, they’ve dealt with a lot of people. You have to establish that you are unique in that group, that you are there to represent what they want. I would tell them they were my boss.”

The importance of actually meeting and talking to children and having them at court to talk to the judge made an impression on Moench. “Through listening, you learn to let people find their own solutions, to let go of what you think is fair and let direction come from your client. Taking complicated legal concepts and explaining them in a way a 7-year old can wrap their head around taught me to be patient, to build that trust, so they would listen to my advice. Building an effective attorney-client relationship is the main thing.”

A key aspect of the CRC is that attorneys representing children in these cases are charged with advocating for their client’s wants and desires. “If a client is verbal and has an opinion, it is our job to make sure they are heard,” said Duke. “In the family code, we are required to represent the express wishes of our clients. We’re the only one representing what the kid wants.” It is up to other parties, such as Travis County or Court-Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) to argue what is in the child’s best interest.

“You learn different ways to handle it when your client wants something that you think is a bad idea,” said Meghan Cook Zuraw, now Dallas program manager for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. “You learn to work with kids to get the best outcome but still fulfill your role, which is advocating for what they want.”

“It is important for kids to have their voices heard,” said Strauch. “So many things are going on in and around them that they don’t control, but ultimately the whole reason a case has been filed is for their protection. We make sure that what they want is represented to the judge, so that, even if they don’t get it, they at least got a fair shake in front of the court.”

Former clinic students say they learned from each other as well as from the faculty and through experience.

“To be honest, one of the pleasures of the clinic was the other students,” said Spechler. “We shared experiences, funny stories, and also very stressful moments. We could commiserate about that.”

The clinic experience also opens doors. “So many of the clinical professors are top in their field, well respected, and true subject matter experts,” said Cook Zuraw. “You can’t get a better recommendation than saying you trained under them.”

As a person who now hires attorneys, Pittman looks for those who participated in a clinic. “I know they are going to have practical experience as well as the knowledge to be an asset to our law firm.”

Overall, McCown says, the CRC has raised the standard of practice in child welfare throughout the state and is widely recognized as providing the best representation to its clients.

In recognition of those accomplishments, in December, 2018, the Child Protection Roundtable, a consortium of more than 70 child welfare organizations statewide, presented the Clinic with its inaugural Madeline McClure Legacy Award for Distinguished Contributions to Child Protection in Texas.

“They’ve been completely on the front lines of child welfare in this state for such a long time,” said Lee Nichols with TexProtects, one of the roundtable members. “This is called the legacy award and we think the CRC has established a fantastic legacy and it was time to recognize that.”

“Nobody goes into this area of practice for the money, but the clinic has made a real difference to a lot of children and youth by providing them a voice in court,” said McCown.