Academic freedom on U.S. campuses has become a much-discussed topic in recent years. So, for those wanting to learn more, seeking out Professor David Rabban is a wise decision.

That’s because he has decades on expertise on the subject. Rabban served as counsel to the American Association of University Professors—the nonprofit membership association of faculty and other academic professionals—for several years before joining The University of Texas at Austin faculty in 1983. Later, Rabban served as the AAUP’s general counsel and chair of its committee on academic freedom and tenure. At Texas Law, his teaching and research focus on academic freedom, free speech, higher education and the law, and American legal history.

In other words, academic freedom has “been an issue I’ve confronted my entire career,” Rabban says.

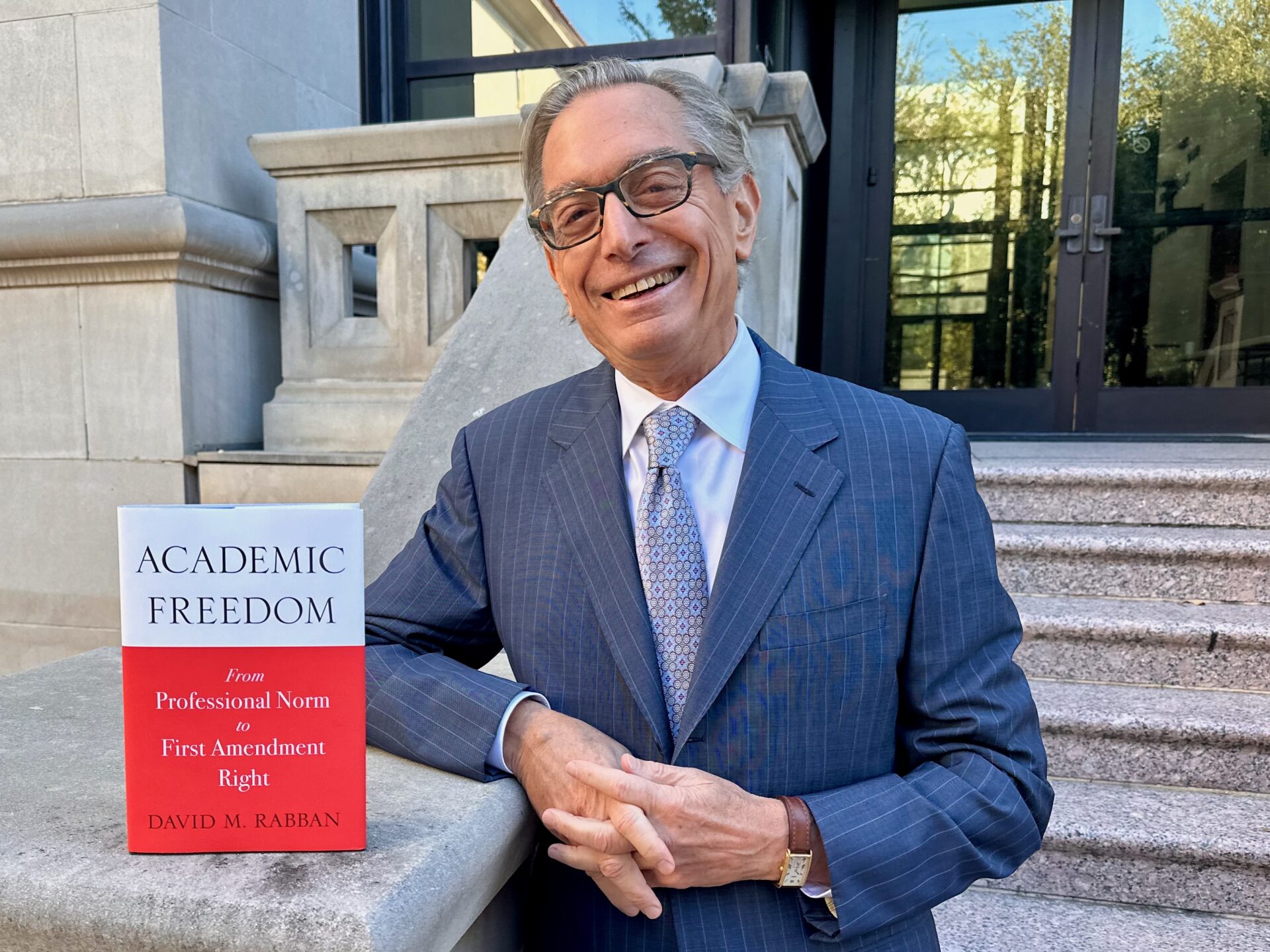

Now, with his new book, “Academic Freedom: From Professional Norm to First Amendment Right,” Rabban dives deeply into the subject of academic freedom as a distinctive subset of First Amendment law, sharing his wisdom for both academic readers and the general public.

Rabban—who is the Dahr Jamail, Randall Hage Jamail, and Robert Lee Jamail Regents Chair in Law—recently discussed his theory of academic freedom, why its protection is necessary for university faculty, as well as the concept’s legal history—and its limits.

You have a long and well-respected career focused on academic freedom. Can you describe when you first began your work in the area?

I started working on cases involving academic freedom as a First Amendment right way back at the beginning of my legal career in the 1970s when I worked as staff counsel in the Washington, D.C. national office of the American Association of University Professors. At the AAUP, I handled a lot of cases dealing with that issue: I argued cases, wrote Supreme Court amicus briefs for the AAUP, and gave professors advice when they asked me about the law related to academic freedom and the First Amendment. So, it’s been an issue I’ve confronted my entire career. Later, I was general counsel of the AAUP and chair of its committee on academic freedom and tenure—positions always held by a full-time faculty member—while working at UT.

With a career full of experience on academic freedom, what prompted you to write this book now? And who do you see as its primary audience?

I wrote an article dealing in part with these issues way back in 1990. But a lot has happened since then—the issue of academic freedom as a First Amendment right has arisen in many more contexts—and I wanted to address them. Also, prior scholars and many judges have complained that the meaning of academic freedom as a First Amendment right is unclear—even though the right is recognized—and I agree with that. So, part of my purpose in writing the book was trying to organize, classify, and clarify the First Amendment law of academic freedom, which I felt would be helpful to the many people working in the area. There are thousands of lawyers who represent colleges and universities in the United States, for example, and there are many professors who are on academic freedom committees at their own institutions. For many people, this is an immediate concern.

That’s a sizable audience on its own!

I also think the topic is of broader interest, not just to people interested in constitutional law, but these days to the public in general. What’s bad for the country is good for my book, in the sense that there are pressures on academic freedom from all over the political spectrum and all kinds of sources, within universities and outside of them. These are very topical issues now. I have heard enough reaction already to know this book addresses the interests of quite a large public.

How do you describe the goal for your readers?

I show where the law is unclear, and I try to offer my own theory about what the First Amendment right of academic freedom should mean.

My book’s subtitle is “From Professional Norm to First Amendment Right.” I decided to emphasize the professional norm because I realized how much more academic freedom has been defined as a concept outside the law than it has been defined as a First Amendment right in constitutional law. The 1915 Declaration of the AAUP, which was written in the first year of its existence, remains the most detailed and convincing justification for academic freedom that exists, and is the source for many institutional regulations about academic freedom today. So, I thought it was important to write about this professional conception.

Much of the justification for academic freedom as a professional norm also is relevant to defining it as a First Amendment right. All too often, lawyers—and especially law professors and judges—harness general policy arguments to constitutional interpretation in ways that seem forced. The policy justification doesn’t always line up with constitutional considerations. But in my opinion, the professional justification for academic freedom, especially in the seminal 1915 declaration, relies on a policy that is also a central First Amendment value. For that reason, I think it’s natural and easy to apply the professional definition to constitutional analysis.

That’s great background to understand. So, how do you apply the professional definition?

Academic freedom for professors is essential to enable them to perform their function that’s in the interest of the entire society: the production and dissemination of expert knowledge. That’s the key justification in the AAUP’s 1915 declaration. The production and dissemination of knowledge is also a central value that appears in many areas of constitutional law, not just in cases involving universities, but in cases involving the press, libraries, and protection of copyright. So, there’s a close relationship, I believe, between the professional definition and the constitutional definition.

To take a step back, why do university faculty need academic freedom?

If professors can be disciplined or fired because their conclusions—based on their expert knowledge and research—offend others, they’re in effect prevented from doing their jobs. It doesn’t make sense to hire professors to use their expertise to search for and disseminate knowledge and then punish them for doing so. And that’s why the First Amendment should protect academic freedom.

Are there limits on a professor’s academic freedom?

The justification for academic freedom is the protection of expert academic speech, so unless a professor is speaking as an academic expert, academic freedom does not apply. All kinds of speech by professors isn’t not about the pursuit and dissemination of knowledge, so they don’t relate to academic freedom. That’s a huge limitation. Also, their speech needs to meet professional standards, as determined by faculty peers: If there’s a dispute as to whether a professor has met academic standards or not, it’s up to fellow experts to determine, because others don’t have the expertise to make the judgment. If a professor of geology says the earth is flat, for example, he can be fired. There are lots of close questions about whether something is within the realm of legitimate academic discourse, but those questions have to first be determined by peer review.

That’s an important explanation. Additionally, you examine foundational court cases in the book. When did the Supreme Court first consider academic freedom?

Although academic freedom was discussed and justified as a professional norm under the AAUP’s 1915 declaration, it only first appeared in majority opinions in the Supreme Court in the 1950s. The cases that first raised issues of academic freedom as a First Amendment right arose in the context of the Cold War McCarthy era and the search for subversive speech and activities. The first major case identifying academic freedom as a First Amendment right was Sweezy v. New Hampshire, decided in 1957.

In that case, Chief Justice Earl Warren’s plurality opinion identified both “academic freedom” and “political expression” as First Amendment rights, which indicated they were somewhat different. He identified and talked about each one consecutively. So that was a very important step, recognizing academic freedom as a First Amendment right, and differentiating it from political expression, though there was no elaboration.

Ten years later, in Keyishian v. Board of Regents, the court majority referred to academic freedom “as a special concern of the First Amendment.” That phrase has been cited in hundreds of subsequent cases. Yet the Supreme Court has never made clear what it means by academic freedom as a First Amendment right. Courts have clearly recognized academic freedom as a First Amendment right, but what it means, how it’s justified, and how it relates to the general First Amendment right of free speech remains unclear, as scholars and judges repeatedly complain. Part of my purpose in writing the book is to differentiate academic freedom from free speech in a convincing, theoretical way.

It’s one of the reasons your book is such an important read. As a Texas Law faculty member, did you get any help from the law school community?

I had three terrific student research assistants while I was working on the book—Alisa Holahan ’15, Sarah George ’20, and Zoe Miller ’23—who helped me find relevant cases and evaluate their importance. I taught a seminar based on drafts of this book, and students had outstanding suggestions that really helped me. One student in particular—Lillian Seidel ’20—suggested I create tables comparing cases by topic, which my publisher didn’t let me put in the book because they made it too long, but did allow a link.

And of course, I talked to my colleagues as I was working on the book. People who are not experts in constitutional law or specialists in the First Amendment provided useful advice. Those who work in other areas of the law were able to ask questions and for clarifications that were very helpful because I wanted the book to reach an audience beyond experts on academic freedom and the First Amendment. Reactions from experts helped, too, especially with respect to more technical issues.

That’s excellent to hear. In closing, is there one thing you’d like your readers to take away from the book?

Understanding and protecting a convincing conception of academic freedom is of vital importance to our society. I wrote this book to try to contribute to scholarship on the important issue of academic freedom. I also tried to make it accessible and readable to a broad public. And I hope I succeeded.