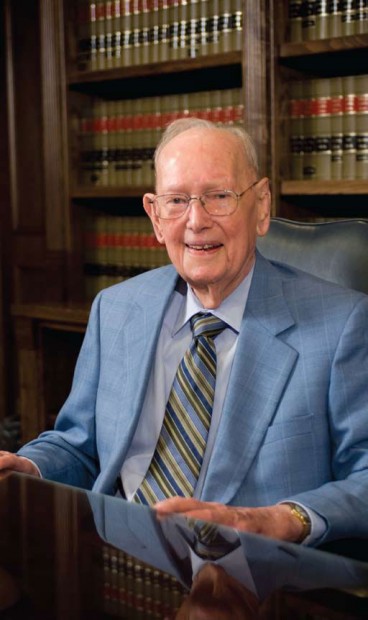

Centenarian Jack Borden, ’36, continues to practice law in his home town.

(Editor’s note: The Law School has received word that Jack Borden passed away January 19, 2011, at the age of 102.)

At age 101, Jack Borden said the happiest day in his life was when he graduated from the Law School in 1936. His diploma remains framed and mounted on his office wall. Borden, the son of a tenant farmer in Weatherford, said he knew his law degree meant his days of thumbing rides and cleaning rooming houses were over—that he had scaled the educational heights and was now a member of that professional triumvirate he esteemed so highly: doctor, lawyer, and minister.

Actually, Borden originally planned on entering the ministry until a childish prank—“baptizing” his black cat in a butter churn—backfired, convincing him to reconsider his vocational ambitions. But Borden never guessed his hard-earned degree would take him so far in the legal field—seventy-three years and counting, first as Weatherford’s assistant district attorney, then district attorney, and later, as a private practitioner.

“Back when I was a law student,” Borden said, “the entire University of Texas had an enrollment of about four thousand to five thousand students. I found classes in contracts and criminal and civil law most interesting. They taught you how to find out specific points of law.” Borden said trial work as a young attorney taught him the rest. He represented clients in both civil and criminal cases—everything from DUIs and burglary to rape and murder—occasionally requesting opinions from the Attorney General’s Office on issues like the lottery and tax assessment. He once defended a client accused of littering by instituting fair turnabout; Borden filed complaints against two city commissioners for the same violation. The city cancelled his client’s fine. As county attorney in Weatherford, Borden foreshadowed his two mayoral terms of office (1960–1964) in the city with the recommendation that prisoners judged guilty of selling liquor illegally should work off their crimes on a chain gang instead of relaxing in cells.

For Borden, a founding member of the nationally-recognized Parker County Sheriff’s Posse, a frontier tradition of hardscrabble existence and independence persisted into the 1940s, fueling a rural law practice distinguished by determination and commitment as exemplified in Borden’s “I-can-do-this” attitude.

Public service was part of that commitment, and that meant relatively low pay. “When I was prosecuting attorney, the limit for my salary was three thousand dollars,” Borden said in Boots to Briefcases: Jack Borden, Country Lawyer, a 2003 book written about him. “The first year, I took in more fees than the three thousand. But I was only allowed to keep three thousand.”

Borden’s sole spell living outside of his hometown was during World War II, when his law enforcement background qualified him for a position with the FBI. After tracking down draft dodgers for several years, he returned to Weatherford and a series of private law partnerships. Borden charged his clients reasonable fees, and never had them sign contracts. But he admitted his current fees for probating wills and handling real estate matters bring in more income than his trial work ever did.

In fact, litigation, which Borden discontinued thirty years ago, triggered obsessive working hours. The cumulative physical stress damaged his health, causing his blood pressure to skyrocket to 210/110. “I ate and breathed every trial,” he said.

Before Borden’s physician gave him a “cease and desist” order, his success rate was nearly perfect. During a ten-day criminal trial involving a proposed cement plant, “I thought my client would be found guilty,” Borden said. His trial strategy, therefore, was to antagonize the district attorney who, Borden hoped, would then commit errors that could form the basis of an appeal. “I knew the indictment was faulty,” Borden said, “But there were twenty-five other errors even though the judge’s reversal was based on only one.” When Borden asked why the judge’s decision cited only the indictment, he replied, “When you’re digging for oil and strike, you don’t take it all—you leave room for more the next time.”

Another example of Borden’s resourcefulness stemmed from his representation of a mother in a custody dispute. “The people were Baptists, and so was I,” Borden said. During the proceedings, “six women sat in the witness room and did nothing but pray. When the other side testified, the husband’s mother naturally told everyone how great her son was. Then I cross-examined her and asked, ‘Are you a Christian?’ She said yes. Then I asked her if she ever prayed about this matter, and she also said yes. Last, I asked what decision she thought was in the best interests of the child.” She conceded Borden’s client should be awarded custody.

“I learned early on that first you sell yourself to the jury; then you sell your clients’ interests,” Borden said. This practical dictum served Borden well, but he also relied on his desire for “challenge” to motivate him. As for the lawyer-client relationship, religion and the Golden Rule—“My parents taught us to treat all people the way we would want to be treated”—influenced most areas, even billable hours.

“I’m amazed at what lawyers charge nowadays,” Borden said, commenting on the profession’s striking changes over the past five decades. “Three hundred to one thousand dollars an hour. No one is worth that kind of money. Everyone wants to get rich. Of course, it costs a lot more today to operate an office.”

Since 1974, Borden’s staff has included his nephew, John Westhoff, whom Borden and his late wife, Edith, put through law school. Westhoff handles Borden’s trial work, videotaping depositions and playing back portions for juries. Although Borden praises his partner’s technological prowess, the centenarian is no PC aficionado. He joked with a reporter that he was still puzzling over the calculator. Yet Borden does not categorically reject new concepts—for example, he endorses legal mediation. “It can save the client money,” he said.

While for many years Borden functioned as a role model (he even prepared his wife for her Bar exam), he admitted that now he has the state and national awards to go along with the title. Borden was recently named Texas and America’s Outstanding Oldest Worker by Experience Works, a nationally-recognized nonprofit training and employment organization. Meticulous preparation, he proclaimed, helped him achieve those honors. “I would say to my nephew, ‘John, when the judge asks you if you’re ready, you better be.’”

Borden still advises his partner from time to time. Once “John was worried that court testimony would reveal something people might see as negative,” Borden said. “He was scared of the jury’s reaction. I told him not to hold anything back—to tell the jury the truth. Then ask jurors, ‘Would you hold that against her?’ The jury later found for John’s client and I attribute this to diplomacy.”

Diplomacy and experience are Borden’s watchwords. To paraphrase one of his favorite injunctions, the secret to harmonious relationships is allowing people to have your way. It also helps to put in a forty-hour week with occasional respites for fishing. With that said, Borden reported that his afternoon schedule called for a meeting with an accountant over an estate and the probating of three wills. “I’ve probated wills for widows for court costs,” Borden said, “But I make enough to pay my share of expenses. So I’m satisfied.”—Janice Arenofksy