A Law School grant helps second-year law student Andrés Durá carry out original research on an 1813 execution for fraudulent bankruptcy in the United Kingdom

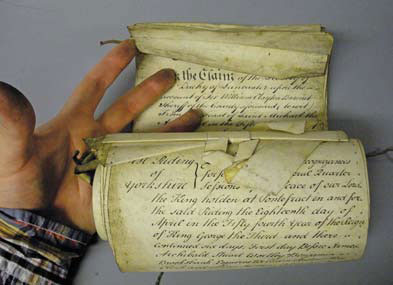

Andrés Durá, ’10, holds York assize records from the United Kingdom’s National Archives in Kew, London, where he carried out historical research on the case of what was likely the last execution of somebody in England for the crime of fraudulent bankruptcy.

Second-year law student Andrés Durá, ’10, was able to carry out some original research in English legal history over the 2008–2009 winter break thanks to a grant from the Law School. Durá was taking Assistant Professor Emily Kadens’ fall 2008 William Blackstone Seminar. During one class, Kadens was discussing the history of capital punishment for fraudulent bankruptcy—a crime in which a debtor conceals assets from creditors—in England, and said the last known execution had taken place in 1761, but that there may have been another, later, execution for the crime in York, mentioned briefly in an 1821 legal treatise by Basil Montagu.

Durá said he immediately thought it might be worth following up on the reference as a possible research topic for the paper he was to write for the seminar. “The original citation in the 1821 treatise just said ‘there may have been’ an execution for fraudulent bankruptcy in York, but no other information,” Durá said. “So I began doing date searches on an English newspaper database for years before 1821, looking for executions in York. I finally came across the 1813 execution of a man named John Senior in York who seemed to fit the criteria.”

Durá compiled a list of people who had been convicted of fraudulent bankruptcy and found that after 1761, though three men were convicted of the crime, only one, John Senior, was listed as having been executed. Durá wrote his paper for Kadens’s class on the use of capital punishment for fraudulent bankruptcy and the eventual change of the statute, in 1820, that allowed people to be sentenced to death for the crime, and turned it in. At the next meeting of the seminar, Kadens asked Durá if he might be interested in studying Senior’s case further and told him the Law School could give him a small grant to travel to the United Kingdom to see if he could locate original documents concerning Senior’s trial and execution.

“It was totally unexpected,” said Durá , who grew up in El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, and who had never visited the United Kingdom before. “This opportunity was very significant to me, because I really didn’t know much about English history, which is really remote for somebody from where I’m from.”

It would not remain remote for long. On December 17, 2008, Durá left Austin for London. “Before I left I tried to isolate possible sources for research,” Durá said. “I found some potentially good leads—one at the National Archives in Kew, a neighborhood in London, and the John Goodchild Collection in Wakefield, West Yorkshire. I took a train from London to visit the Goodchild first, but it initially turned out to be a false lead. The manuscript I was looking for was about a different John Senior who had beaten his apprentice.”

But Durá’s trip to Yorkshire was not fruitless. Durá made the acquaintance of John Goodchild, who runs the eponymous historical collection. “He gave me an impression of the local history, and helped me find out where the John Senior I was looking for lived. We found two properties under his name and Mr. Goodchild showed me that my research would have to be broader, more general, to help narrow down where he might be from. We found out that Senior did not own the properties, but occupied them through some sort of agreement with some upper-strata people. He lost some of their money at horse races in Doncaster, and then committed fraud to get the money back. Mr. Goodchild allowed me to look through his index and try to find all the names in his case. We didn’t find any more, though. Most were relatives. It was very interesting, though. I think Mr. Goodchild wondered what a person from El Paso was doing there, asking him all these questions. It was a good cultural exchange.”

Durá next went to regional archives in York, where he found a calendar of prisoners and executions from the period in which Senior was executed. “In York, they still have the drop where prisoners were hanged at York Castle, which is now a museum. I spent a couple of days there researching their archives and found some original sources where my secondhand information had come from. But the leads I had come up with in Austin turned out to be false as well. It’s hard doing this sort of work, because only about five percent of bankruptcy records in England from the period survive.” Durá said further research at the National Archives in London led to finding a book with details on Senior’s trial and verdict, including the fact that one of the lawyers representing Senior was related to the owner of one of the properties listed under Senior’s name. Durá also found a report on the trial that said Senior’s apparent accomplice in fraud had become one of the witnesses against him.

Durá said many of the questions he had about Senior’s trial—what the particular circumstances that caused him to be probably the last man executed for fraudulent bankruptcy in England were–proved difficult to answer before he returned to Texas on January 7, 2009.

“Two or three more weeks there would have uncovered some more details, possibly, and genealogical research would be the best way to find out who his petitioning creditors were,” Durá said. But he said he gained valuable insight into the legal and cultural environment that led to the eventual discontinuance of capital punishment for fraudulent bankruptcy in England. “In a sense Senior’s case is an example of exactly the type of behavior that the bankruptcy statutes of the time were meant to deter,” Durá said. “But his punishment was so severe that you can’t help but feel sorry for him. As Montagu argued, one fundamental problem with the statutes was that they did not account for the coresponsibility of the creditors in issuing out their loans more responsibly.”

Durá also found that the death penalty for fraudulent bankruptcy was so uncommon that Senior would have had some reason to think it would not be applied in his case. B ut beyond the pleasures of poking around in overseas archives and immersing himself in history, Durá said he learned important lessons beyond the particular circumstances of John Senior’s long-ago execution. “The seminar and the trip that resulted from taking the class helped me understand the underpinnings of our American common law system much better,” he said. “It was the perfect way to get to know first-hand the history, people, and events that shaped our modern legal system. It also changed my approach to legal education by providing a context through which I can evaluate how our contemporary legal institutions work.”

Durá said he has primarily been interested in legislative and immigration legal work, and has participated in the Transnational Workers Clinic at the Law School, but that his research experience has opened up the possibility of pursuing a teaching and academic career, as well. “It made me aware of things I like doing,” Durá said. “Going to the sources, doing detective work. Whatever I do I’d like it to have these elements. I’m grateful to everyone who made this life-changing experience possible and look forward to the rest of my legal education with a renewed sense of confidence and meaning for my legal career.”