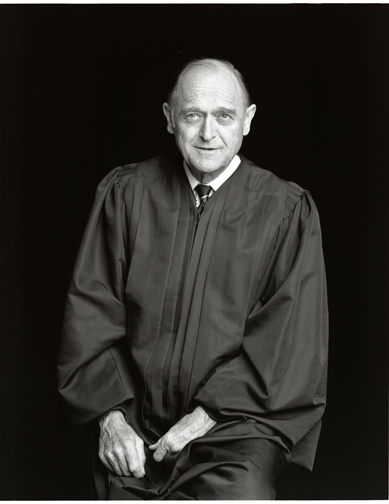

William Wayne Justice, ’42, passed away on October 14, 2009, but his legacy lives on at the Law School. This April, The William Wayne Justice Center for Public Interest Law, which is named after the famed judge and recently celebrated its fifth year of trying to further his commitment to public service and equal justice, sponsored a variety of events in his honor. On April 15, a panel discussion, “The Arc of Justice—The Legacy of Judge William Wayne Justice and the Role of Lawyers in Social Reform,” was held at the Law School. On April 16, “Celebrating Judge William Wayne Justice’s Life and Legacy” took place at the Darrell K. Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium. Speakers included Law School Dean Larry Sager; students Lawson Konvalinka, Jordan Pollock, and Kyle Marie Stock; Judge Royal Ferguson; and lawyers Eric Allbritton and David Weiser. Later that day, a cenotaph was dedicated in Justice’s memory at the Texas State Cemetery. His daughter, Ellen; former State Senator Gonzalo Barrientos; Judge John T. Ward; and lawyer Richard W. Mithoff, ’71, spoke.

Mithoff, a Houston lawyer who clerked for Justice after he graduated from UT Law, has himself done a great deal to further his mentor’s legacy, helping to fund the Law School’s new school-wide pro bono program. Mithoff was the last speaker at the cenotaph dedication, and his eulogy is reproduced here.

Judge William Wayne Justice came to the bench just two months after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and for the next forty years, his name would come to be associated with the most far-reaching civil rights decisions of the last half century. To fully understand his commitment to civil rights—to fully understand the man who became the judge—we have to look back, I believe, to how he began and to the events that shaped his life.

We have to look back in time, as if squinting at the spliced pieces of a very old black-and-white film, to see the images that he brought to life for all of us who came to know him. We see a very young child confined to his home in Athens, Texas, by three bouts of pneumonia and one near-fatal case of whooping cough. He would later say these conditions left him “as weak as water” and subjected him to taunting and teasing by his friends at school, but they also left him with time to read every book he could get his hands on: histories of the South, biographies of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson and Jefferson Davis, and the entire eight volumes of the family encyclopedia.

We see a child standing in the backyard of his home during the Great Depression, watching a freight train rumbling past, with hungry, desperate men clinging to the boxcars, and we watch as many of these same men later, one by one and sometimes in small groups, would come by the house where his mother, Jackie May Justice, would feed them and listen to their stories.

“I never did see my mother turn down a single one of them,” he would later say. “About the only thing that it cost them was that she liked to hear their stories. She was always very interested in where they were from, if they had a family they’d left behind.”

We see a child at play with two other children— one white and one black—lost in a world of make-believe that is shattered when the mother of the white child calls out to her son, and he repeats the words to the others, and then they watch the little black boy walk slowly away, an image that is fading on our film now because it has been replayed so many times.

“I think it was very early in life that I saw injustice,” he would later say. “I remember when I was about seven or eight years old, I was playing with one of my white friends in a vacant lot. And a little black boy about our same age came along, and we were playing together. About that time there was a knock on the window. The mother of this other child was knocking on the window to attract our attention. My white friend went in to talk to his mother and he came back and told us he couldn’t play with this boy, using a racial slur for Negro. So that little black boy went off. I think that might have been the first time that I decided that things weren’t exactly right. You know, any child growing up in a Deep South atmosphere is going to be aware that there’s something different between the races. but I think that’s the first time I ever viewed it as something bad. I’ve often thought about it.”

We see a young man as he follows his father to the courthouse and watches in awe as the great Will Justice holds a jury spellbound by his scathing cross-examination and soaring oratory, and we watch him as he follows his father home again to watch the defender of the downtrodden prepare for the next day, propped up on pillows in his bed with the file and a cigar and a box of matches, cigar ash tumbling down his open vest and onto the bedcovers.

As a prosecutor, Will Justice secured convictions in all but one of 156 cases he took to a jury, and as a defense attorney, he handled more than two hundred capital cases and never had a client receive more than forty years as a sentence. It was said then that “[t]here is no justice in East Texas except Will Justice.”

He once encountered a man on the street beating a helpless dog and confronted the man, separated him from the dog, and immediately marched over to the office of the District Attorney and insisted on being commissioned as a special deputy attorney to personally prosecute the offender. He obtained a conviction for cruelty to an animal with the maximum fine and later told his son that he had never had a prouder moment as a lawyer.

We then fast-forward and see Judge Justice as I did one day during my clerkship almost forty years ago when we went to the Gatesville School for Boys to tour the state facility in a case challenging the treatment of juvenile offenders. And we watch him walk from cell to cell in the cold, damp, maximum-security unit, interviewing young boys—trembling, sweating, eyes darting nervously. Each in solitary confinement and each recounting stories in chilling detail of being tear-gassed in their cells, of being chained together and forced to march across a field picking at the earth in a meaningless exercise, of being beaten and tortured and raped. We said very little to each other on that long drive from Gatesville back to Tyler.

I had watched his eyes before, had seen him on the bench peering over those little half-glasses, staring down at some redneck deputy sheriff on the witness stand, with the only sound in the entire courtroom coming from the squeak in the swivel chair as the witness squirmed under questioning from the bench, and I had watched his eyes again that day as we emerged from maximum security, but this time I saw eyes that appeared to blink away a tear, weary of the parade of brutality and cruelty bigotry and hate.

I thought much later of Atticus Finch, the country lawyer in Harper Lee’s masterful story, who is appointed by the local judge to defend a black man charged with the rape of a white woman in a small town in the South in the forties, and of the torment and threats of violence he and his family endured. And of Scout, his little girl, through whose eyes the story unfolds, as she turns to the woman next door to try to understand why it is that her father had to be the one to defend this man.

“[T]here are some men in this world who were born to do our unpleasant jobs for us,” she says. “Your father’s one of them.”

Perhaps it is true, as some have suggested, that we would not want every judge to be William Wayne Justice. I know it is true that we are indeed blessed to have had one judge who was.—Richard Mithoff, ’71