Every summer, UT Law students carry out public-interest legal work thanks to internships and fellowships funded by donations to the Law School. We will be adding more stories about our Summer 2012 Fellows and the work they did over the coming weeks, so check back often.

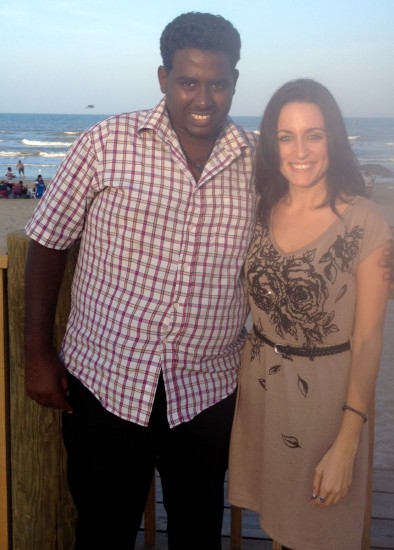

Fighting for the Human Rights of the Mentally Ill: Mark Dawson, JD expected 2014, at Human Rights Law Network in Mumbai, India

As a Rapoport Center Summer Fellow, Mark Dawson spent his summer in Mumbai, India, working with the Human Rights Law Network. That placement allowed him to work on an issue that attracted him to UT Law School in the first place—the role of human rights law in the developing world.

During his time in Mumbai, Dawson worked on what in India is called Public Interest Litigation (PIL)—Indian law similar to class-action suits in the U.S.—that went directly to the Bombay High Court, an original jurisdiction and appellate-level court. The Human Rights Law Network of Mumbai pursues a number of PIL cases, and while in the country this summer, Dawson worked on a brief aimed at repealing India’s Mental Health Act, a law that he characterizes as based on the “clearly outdated and draconian 1912 Lunacy Act of Britain.”

“The Mental Health Act of India treated persons living with mental illness as less than full citizens,” he said. “Their rights to refuse to treatment, leave the hospital, or own property are for the most part eviscerated in law. In practice the situations is worse. The law has multiple loopholes that make it easy for family members or friends with money to have others declared mentally incompetent and locked up. The worst part of the law is that persons who seek voluntary treatment cannot thereafter leave if they want to. Another bad part of the law is that it contains no provisions regulating the use of electro-convulsive therapy (ECT). Once a patient is admitted to these institutions they are regularly given heavy doses of psych tropic drugs and ECT, treatments which are both harmful and unnecessary.”

Dawson took advantage of the resources that come with being a UT Law student in his work on the brief: “I contacted a UT professor during the summer who was an expert on the subject,” he explained. “I’d never talked to him before, and I didn’t have him as a professor, but he wrote me back with great advice.”

The attempt to repeal the Mental Health Act is an ongoing one, and Dawson’s ten weeks saw him leave the country with the litigation still undecided. But what he learned during the process was something that he can take with him as he begins his career in international human rights law. “Something my boss said to me is, ‘Mark, we don’t argue the law to the judges. We argue compassion to them first,’” Dawson recalled, explaining, “Only if they care do we get the opportunity to argue the law. Even if the law is on our side—the poor too often lose in India. We file anyway because sometimes we win.”

Moreover, after spending the years following his undergraduate degree working on community development projects in Africa, Dawson saw firsthand a major problem in the developing world. “I saw on a systemic level that even if you come up with the best development plan it will still fail if there’s corruption,” Dawson explained. “But lawyers can do this incredible thing that no one else can do [combatting corruption]. And people told me that I’d be pretty good at it.”

Three Months in the Valley: Mary Chisolm, JD expected 2015, spent a summer working for civil rights on the Texas-Mexico border

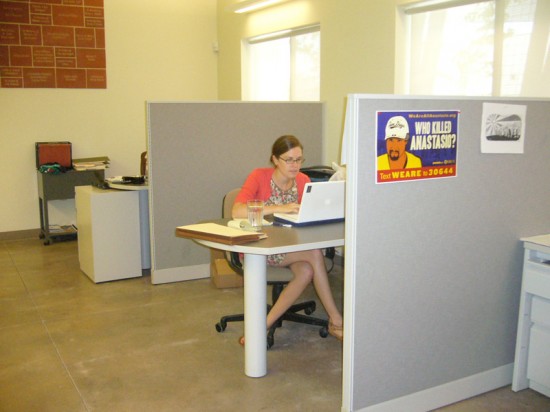

Baron & Budd Public Interest Summer Fellow Mary Chisolm, ’15, working at the South Texas Civil Rights Project in Alamo.

Before coming to the Law School, second-year student Mary Chisolm worked and volunteered with a variety of underserved groups, from afterschool tutoring at low-performing schools in Austin to building houses in Mexico. “That kind of work led me to want to do something really tangible,” she said. “I saw all these groups that I wanted to help, but as an English major there wasn’t much I could do.”

Chisolm’s determination to make a tangible difference for underserved populations led her first to UT Law, and, once there, to a Baron & Budd Public Interest Summer Fellowship at the South Texas Civil Rights Project (STCRP) in Alamo, Texas. “I learned about Texas Civil Rights Project in general and thought their mission lined up pretty much one hundred percent with the reason I wanted to go to law school,” Chisolm says. “I also really want to work with Hispanic immigrants, so that was a good way to get experience.”

This summer, Chisolm’s work at the STCRP included a Violence Against Women Act petition, a property law case for an undocumented client, and several Americans with Disabilities Act suits. She credits the fellowship with sharpening her writing skills and her understanding of how a case is built. “Watching the attorneys when we had potential clients call, and learning the process through which they decide—is this a case that’s going to be successful? Will we have a good chance of winning? Will it have a big impact on the community?—just getting to learn more about that decision-making process was really helpful,” she said.

Chisolm said her experience at the STCRP has made her even more certain of her commitment to a career in public interest law. Her favorite element of the summer work was getting to see and participate in a large, supportive network of activists and community groups in the Valley doing tangible good. “All the different types of organizations work really well together to support worker’s rights and rights for immigrants,” she said. “It was an exciting thing to be a part of.”

The Baron & Budd Public Interest Summer Fellowship is supported by generous funding from Baron & Budd PC.

Baron & Budd Public Interest Summer Fellow Whitney Drake, left, and Whitehurst Public Interest Summer Fellow Hannah Zimmermann at the American Gateways offices in Austin.

Making Way to Safety: Whitney Drake, JD expected 2014, and Hannah Zimmermann, JD expected 2013, at American Gateways in Austin

American Gateways is a nonprofit organization in Austin that provides legal and educational services to immigrants fleeing violence and war in their home countries in search of a safe home in the United States for themselves and their families. Whitney Drake, Baron & Budd Public Interest Summer Fellow, and Hannah Zimmermann, Whitehurst Public Interest Summer Fellow, spent the summer assisting American Gateways clients with the immigration process.

Both students collaborated with American Gateways lawyers on asylum cases for clients who had traveled to the U.S. in search of safety from persecution based on their race, religion, social group, nationality, or political opinion, among other things. Drake and Zimmermann gathered information to support their client’s claims, drafted briefs, and researched country conditions. Both Drake and Zimmermann were able to communicate with Spanish-speaking clients in their native language.

“I searched through U.S. and Mexican government documents, U.S. and Mexican newspapers, and NGO reports from the 1990s until present-day, with a special emphasis on present-day conditions,” Drake said about one of the cases she worked on. “I was able to hand the judge four hundred pages of collected data to prove that physical abuse was still occurring.”

One of Zimmermann’s clients traveled through seven countries to get to the United States. Zimmermann researched country conditions to see if her client would encounter persecution for political resistance if returned to her native country of Nepal.

Drake and Zimmermann also obtained police records, country documents, and even spoke to friends and family of the clients.

“What really struck me is that in a lot of cases, the systems to navigate immigration law are really complicated. Immigrants have the right to an attorney, but most can’t afford a private practice attorney,” Zimmermann said. “I enjoyed being able to help these people that don’t have the access to help that citizens do.”

“During the removal process, many clients have to remain in a detention center that is, in most respects, similar to jail,” Drake said. “American Gateways provides know-your-rights presentations to this very underserved detainee population.”

The students’ projects were carried out under the guidance of their supervising attorney, Virgil Carstens. Carstens was impressed by the compassion and legal analysis from both Drake and Zimmermann. “They just took the ball and ran with it,” Carstens said. “Both did a tremendous job that will have a great impact on our clients’ lives.”

Zimmermann’s fellowship was funded by Bill Whitehurst, ’70, and his wife Stephanie. Drake’s fellowship is funded by a gift from Baron & Budd PC. Both fellowship programs are administered by the Law School’s William Wayne Justice Center for Public Interest Law.

Learning First-hand about International Human Rights Law: Alejandra Avila, JD expected 2014, at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights

Alejandra Avila, recipient of the 2012 Charles Moyer Summer Human Rights Fellowship awarded by the Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice, spent her summer in San Jose, Costa Rica, working as an intern for the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the autonomous judicial institution set up by the Organization of American States to enforce and interpret the provisions of the American Convention on Human Rights. Avila conducted legal research and aided in the drafting of judicial decisions in international human rights cases adjudicated by the Court, giving her the opportunity to work with lawyers and human rights experts from across Latin America and learn about the intricacies of human rights law.

“I worked in a team composed of a senior attorney from Argentina, a junior attorney from Mexico, a professional visitor from Ecuador, and an assistant from Costa Rica,” Avila said. “I researched jurisprudence of the Court and other international tribunals and drafted memos on issues such as the death penalty, extrajudicial killings, sexual violations, torture, and due process. I also attended public hearings, met the judges, and had the opportunity to work with interns and experienced attorneys from all around the world.”

The opportunity to be exposed to multiple areas of the law also impressed Avila. “It was interesting to see what other interns and the attorneys brought to the table,” she said. “Human rights is such a broad area in law that I had the opportunity to work with professionals in areas such as environmental law, criminal law, immigration, civil litigation, and constitutionalism. Everybody contributed with different ideas in their respective areas of expertise, yet everybody was equality passionate about the work we were doing.”

Avila hopes to pursue a career in public service, and said her experience at the Inter-American Court will help her no matter what particular career path she chooses to follow. “I had the opportunity to work in a multicultural setting on issues that I feel very passionate about,” she said. “It was challenging but very rewarding. I learned about public international law and the role of the Court and also got to work on my legal Spanish. I plan to make public service and pro bono work a big part of my legal career.”

Avila’s fellowship was made possible by the generous contribution of Scott Hendler of HendlerLaw PC, an international plaintiffs’ trial firm based in Austin. Hendler completed the first post-graduate internship at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in 1983-1984 under the supervision and guidance of then Secretary of the Court Charles Moyer. Hendler established the fellowship to honor the guidance and influence his life-long friendship with Moyer has had on him by enabling law students to advance the goals and values to which Moyer has dedicated his life.

Working with Austin’s most vulnerable laborers: Dave Mauch, JD expected 2014, at the Equal Justice Center

Low-wage workers, especially immigrants, often believe that they have no legal recourse when they are paid less than minimum wage—or aren’t paid at all—for their work. Though in fact they do have the legal right to be paid properly, practically speaking they often face the additional problem of having nowhere to turn for help enforcing their wage rights. Austin’s Equal Justice Center (EJC) was founded in part to help people who might normally be afraid to complain to the authorities about labor violations—whatever their immigration status.

“Most legal services organizations don’t provide this kind of legal assistance both because they lack employment law expertise and because of funding limitations on representing immigrants,” said Dave Mauch, a second-year student at the Law School who interned with the EJC last summer as a Whitehurst Public Interest Summer Fellow. “That’s really what makes the EJC unique.”

Under the supervision of EJC attorneys, Mauch got involved in every aspect of the employment rights litigation process—from intake interviews to filing lawsuits, all the way through the discovery phase, to settlement negotiations and settlements. Over the course of the summer, Mauch grew as a young lawyer-to-be, particularly in the area of client interaction. His experience at the EJC helped him decide to pursue an active litigation practice in addition to policy work. In law school, he said, “It’s easy to see litigation in this bubble that doesn’t involve the client’s interest. The extensive interaction I had with our clients helped me develop valuable skills that I’ll use as an attorney.”

Another favorite aspect of Mauch’s fellowship, was interaction with opposing counsel. One of Mauch’s cases at the EJC had him working opposite a seasoned attorney in a prevailing wage case. One morning, Mauch arrived at the office and immediately fielded a heated phone call from the lawyer pressing a mistaken legal position. “Having that experience really helped me learn how to deal with opposing counsel in a effective and professional manner, and how to use interactions with opposing counsel to further goals in the litigation process,” Mauch said. It was a taste of the big leagues, an adrenaline boost that Mauch hopes will launch him to a career fighting for the voiceless and the disempowered.

Mauch’s fellowship was funded by Bill Whitehurst, ’70, and his wife Stephanie, and administered by the Law School’s William Wayne Justice Center for Public Interest Law.

Assisting Asylum Seekers: Nikiya Natale, JD expected 2013, at ProBAR

As a 2012 Whitehurst Public Interest Summer Fellow, Nikiya Natale worked with the South Texas Pro Bono Asylum Representation Project (ProBAR) in Harlingen, Texas, helping represent detained immigrants and asylum-seekers at the Port Isabel Detention Center.

ProBAR, a joint project of the American Bar Association, the State Bar of Texas, and the American Immigration Lawyers Association, provides pro bono legal services to detainees in South Texas.

Natale worked with immigrant detainees from all over the world on a variety of types of cases, primarily asylum applications. One of her clients walked across the Horn of Africa, then traveled using various means to the United States/Mexico border, to escape political persecution in his home country.

“Asylum seekers generally present themselves at the border,” Natale explained. “They state their request for asylum, and are then sent to detention centers while their cases are processed. There is a serious backlog of cases, so sometimes detention lasts for months.”

The first step in the process is the “credible fear” interview, which is used to establish the merits of the individual’s claim. Should they pass the interview, they must then prepare for a series of hearings and the asylum application. The final hearing requires extensive documentation supporting their request for asylum. Obtaining these records can be a fairly complicated process.

“It’s often not easy to get this documentation,” she said, describing difficulties including language differences and navigating foreign bureaucracies. “But somehow it gets done.”

Under the careful supervision of ProBar attorneys, Natale helped her client prepare for his final hearing, which required documentation in excess of three hundred pages. The types of documents included letters of support from friends and family, proof of identity, numerous country condition reports, an affidavit, and a short legal brief, among others. The date for his asylum hearing was set, and Natale extended her stay in Harlingen by several weeks so she could appear at the hearing.

“The Judge commended her on her preparation of the case,” said Meredith Linsky, Director at ProBar and one of Natale’s supervising attorneys.

As a direct result of her efforts, Natale’s client was granted asylum. He will spend the next few weeks finalizing his paperwork before he heads to California to live with family friends.

“Nikiya was a real gift to this office,” Linsky said. “Her commitment to immigration law is tremendous.”

Strengthening Due Process Protections: Salima Pirmohamed, JD expected 2013, at the Texas Defender Service

As a Whitehurst Public Interest Summer Fellow at the Texas Defender Service in Houston, Salima Pirmohamed assisted with the drafting of a federal court petition and clemency application for Yokamon Hearn, a client of the nonprofit law firm until he was executed on July 18, 2012.

Hearn wasn’t wrongfully convicted, but Pirmohamed believes there were mitigating factors in his case that should have merited a stay of execution—notably, that he suffered severe impairments from brain damage.

“In most law offices, the work isn’t a case of life and death,” said Kathryn Kase, executive director of Texas Defender Service. “Here, it is.”

Established in 1995, TDS represents death-row prisoners. The firm’s mission is, in part, to identify and correct procedural issues that can result in inequalities and thereby strengthen due process protections in the Texas criminal justice system.

“Death penalty work can be tremendously complicated procedurally,” said Kase. “But there is no better way to see how cases can go wrong. How undeserving people can end up on death row. Our work shows how people fall through the cracks, how justice is not served.”

An important aspect of TDS’s work is telling their clients’ stories in ways the public can understand, to illustrate the types of policy reforms that are needed to strengthen due process protections. So although Pirmohamed is not yet a licensed attorney, her contributions over the summer were considerable. She used her legal writing and research skills to help document the facts of Hearn’s life, focusing on the lawyers that represented him in his state and federal habeas proceedings.

“I’m glad I was able to give voice to his claims and his case,” said Pirmohamed. “Telling these stories helps everyone understand what poor lawyering yields. I find the work fascinating and outraging. There are cases where many things go wrong, but these things can be corrected. Change is possible.”

Whitehurst Public Interest Summer Fellowships are made possible by a gift from Bill Whitehurst, ’70, and Stephanie Whitehurst, and are administered by the Law School’s William Wayne Justice Center for Public Interest Law.

Standing Up for Victims of Misconduct: Joanne Heisey, JD expected 2013, at the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division

Spending this summer as a Public Service Fellow had Joanne Heisey working what she describes as her dream job—in Washington, D.C., as an intern at the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division. Heisey worked in the Special Litigation section, which focuses mostly on cases with a pattern of Constitutional violations in police departments and correctional facilities. For her, the opportunity to stand up for people who are the victims of misconduct from those empowered by society to protect them is part of what inspired her to attend the Law School.

“I knew that I would want to use my law degree to advocate on behalf of people who are powerless,” Heisey said. “When you’re coming against the police, victims of misconduct oftentimes come from vulnerable populations, so those people certainly need an advocate on their behalf.”

While Heisey has done similar work in nonprofit settings in the past, the experience of approaching these issues as part of the Department of Justice was eye-opening. “I really liked seeing it from the government side,” she said. “They can come at it with a bit more of a heavy hand; police departments are more apt to listen when it’s the federal government filing suit against them.”

As part of the internship, Heisey spent much of her time doing legal research and writing, mostly on Fourth Amendment claims dealing with search and seizure and unreasonable force, as well as analysis of data from police departments. After analyzing the stops that the departments under investigation did, and reviewing citizen complaints looking for patterns, Heisey would apply her legal research to the patterns that she found.

“There was a case where the pattern was that citizens had complained of unconstitutional stops and searches, targeted at populations living in subsidized housing, and mostly African Americans. City officials had made not very well-disguised comments that they were not welcome, and about their desire for the public housing to be shut down,” Heisey recalled. “I got to read a lot of the citizen complains that had been lodged against the department, and it seemed like there was real intent behind the constitutional violations.”

Heisey is aware that pursuing her passion by working on cases like this isn’t necessarily the key to post-graduation riches—“There’s not a lot of money in suing police departments,” she laughed—but it’s important work to her. “I just see it as a major injustice, when police abuse their authority. In these cases, the powers-that-be really need to see that they can’t do this.”