Oscar Salinas, JD expected 2014; Wei Zhao, ’12; and Lucille Wood knock on the door of a house in a colonia in Cameron County to gather information about the prevalence of contracts for deed for a study requested by the Texas Sunset Advisory Commission. The students volunteered for the work as part of the 2011 Pro Bono in January trip.

Many of Texas’s poorest residents, perhaps half a million according to some studies, live in colonias—a Spanish term referring to informal housing settlements located near the Texas-Mexico border. Similar communities, known as “informal homestead subdivisions,” exist on the outskirts of cities in the interior of Texas. Residents of these communities often endure difficult conditions such as the lack of reliable plumbing or electricity and shoddy housing construction. But they also often endure the risks and financial dangers that come with a lack of a bank-financed mortgage on their property. Many colonia residents buy their land through “contracts for deed,” which are often issued by the original property owners as “pay to own” contracts, and may be as informal as a handwritten deal written on notebook paper.

In 2011, the Texas Sunset Advisory Commission requested that the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs commission a study to assess the prevalence of contracts for deeds in colonias. Peter M. Ward, C.B. Smith Sr. Centennial Chair in US-Mexico Relations at the LBJ School; Heather Way, ’96, director of the Law School’s Community Development Clinic; and Lucille Wood, 2011–2012 Research Fellow at the William Wayne Justice Center for Public Interest Law, were contracted to direct the study.

The informality of contracts for deed means that colonia residents are often at risk of unclear title to their homes, which can complicate sales immensely and put property owners at great risk. “Buyers risk losing their properties, their homes, and all of the money they’ve put into those properties and homes,” said Wood. “Everything.”

Students from the Law School, the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, the Department of Sociology, and the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies used their 2011 Winter Break to travel on the “Pro Bono in January” trip in order to gather data for the study. They knocked on doors—occasionally avoiding stray dogs!—in colonias in Cameron, El Paso, Hidalgo, Starr, and Webb Counties to interview residents about their living conditions and the nature of their property contracts. They also conducted wills clinics to help residents gain clear title to their properties. A later phase of the study sent students and researchers into communities in Maverick County and into Central Texas informal settlements. The study gathered and analyzed data from 1989 to 2010.

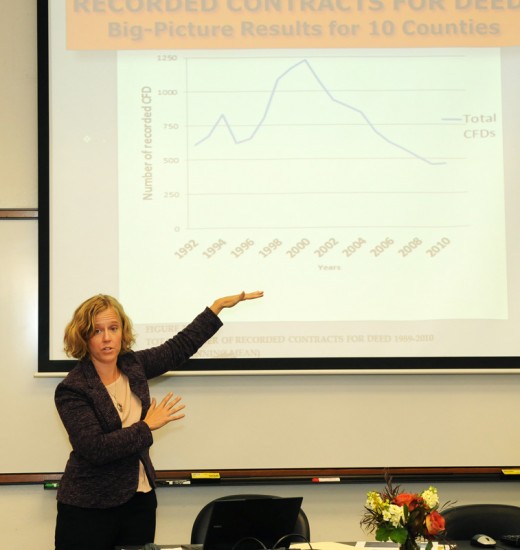

Justice Center Research Fellow Lucille Wood presents findings of the

Contract for Deeds Prevalance report at a press conference at the Law School on October 19, 2012.

“I was impressed by the willingness of the residents to share their time and personal information with us,” said Tecuan Flores, JD expected 2014, one of the Law School students who gathered research. “The surveys were rather involved, but very few people declined to partake in the survey or asked to skip questions. It was great practice explaining the surveys to the homeowners and establishing enough trust to get them to participate. I was most surprised by the high mortgage interest rates we encountered, some reaching eighteen to twenty percent APR. For me, this highlighted a tension between the dream of home ownership and the extreme costs some pay to achieve the dream. Some of the families would have been better off financially by renting rather than purchasing homes through high interest rate mortgages and the added risks of purchasing with a contract for deed. One case that was particularly rewarding for me was explaining a late payment penalty to a family we surveyed. Their monthly mortgage payment was approximately two hundred dollars, but they were paying an additional ‘late penalty’ each month. The family did not understand that the late penalty could be avoided by paying on the first of the month instead of the middle of the month. No one had explained the penalty to them, and for the past two years they were unnecessarily paying the late payment penalty. It was only by looking through their paperwork to answer survey questions that this issue surfaced. I learned there is a lot we can do to help these communities.”

The research was extensive. “We visited more than thirteen hundred households to examine whether and how low-income buyers in Texas’s poorest communities are obtaining title to their land, with a specific focus on the use of contract for deed,” Way said. “Texas lawmakers were concerned with the rampant use of contracts for deed in land sales to low-income homebuyers in colonias, and passed legislation in the mid-1990s to afford buyers greater protections. This report is one of the first major studies to chronicle land transaction practices in colonias since the passage of the legislation.”

Lucille Wood, 2011–2012 Research Fellow at the William Wayne Justice Center for Public Interest Law; Peter M. Ward, C.B. Smith Sr. Centennial Chair in US-Mexico Relations at the LBJ School; and Heather Way, ’96, director of the Law School’s Community Development Clinic oversaw research into the prevalence of “contracts for deed” in Texas colonias and informal housing settlements.

Ward, Way, and Wood presented the findings of the study at a press conference at the Law School on October 19, 2012. They presented three key findings. First, the mid-1990s legislation has steered many developers away from using contracts for deed. However, some developers and investors in new developments who have opted to issue traditional warranty deeds are repossessing land from buyers in colonias with foreclosure rates that far surpass national rates. Buyers in these developments are living in some of the poorest housing conditions in Texas.

Second, unrecorded contracts for deed are still prevalent in land sales by former residents, placing buyers in vulnerable positions. “One in five families in the study recently bought land using an unrecorded contract for deed and thus do not have formal title to their properties,” Way said. Finally, the report warns of a likely rise in title problems. “A lot of families are inheriting property outside of the probate system,” Wood said. “Nine out of ten households in the study do not have a will.” It all adds up to a looming problem for the Texas counties who will have to sort out the intricacies of these complicated and often unrecorded title transfers and the disputes among heirs and owners that will inevitably accompany some of them. “There are going to be more and more problems in the future as titles continue to become clouded by unrecorded contracts,” Wood said. “On top of that, many of the families we studied have had divorces, and multiple children from different marriages. Each of these factors will make it extremely difficult, as large numbers of current owners die without wills, for clear titles to be established.” Since the study was commissioned by a Texas state agency, the report offers many different policy ideas for resolving issues surrounding the contract for deed and land titling issues.

“The recommendations are focused primarily on streamlining and modernizing the current land titling systems, and looking at ways to better educate and serve the interests of homeowners who have bought property under contract for deeds,” Way said. Among the recommendations is reforming Texas counties’ land record system. The study also recommends providing deed and deed of trust templates to property owners to prevent informal and possibly invalid or misleading handwritten contracts; and legislation to automatically convert contracts for deed to warranty deeds or deeds of trust, thus reforming the state’s current conversion program. The study also suggests the Texas Legislature consider setting up a task force to examine ways to increase the use of wills and improve access to the probate process for low-income heirs, among other proposals. “Better consumer education, a lower interest rate cap, and increasing access to credit—perhaps through communitybased lending institutions—would all help low-income home buyers better secure title to their property, and that would help State and county governments prevent some of the problems we see developing as a consequence of not addressing these title issues,” Way said. —Julien N. Devereux