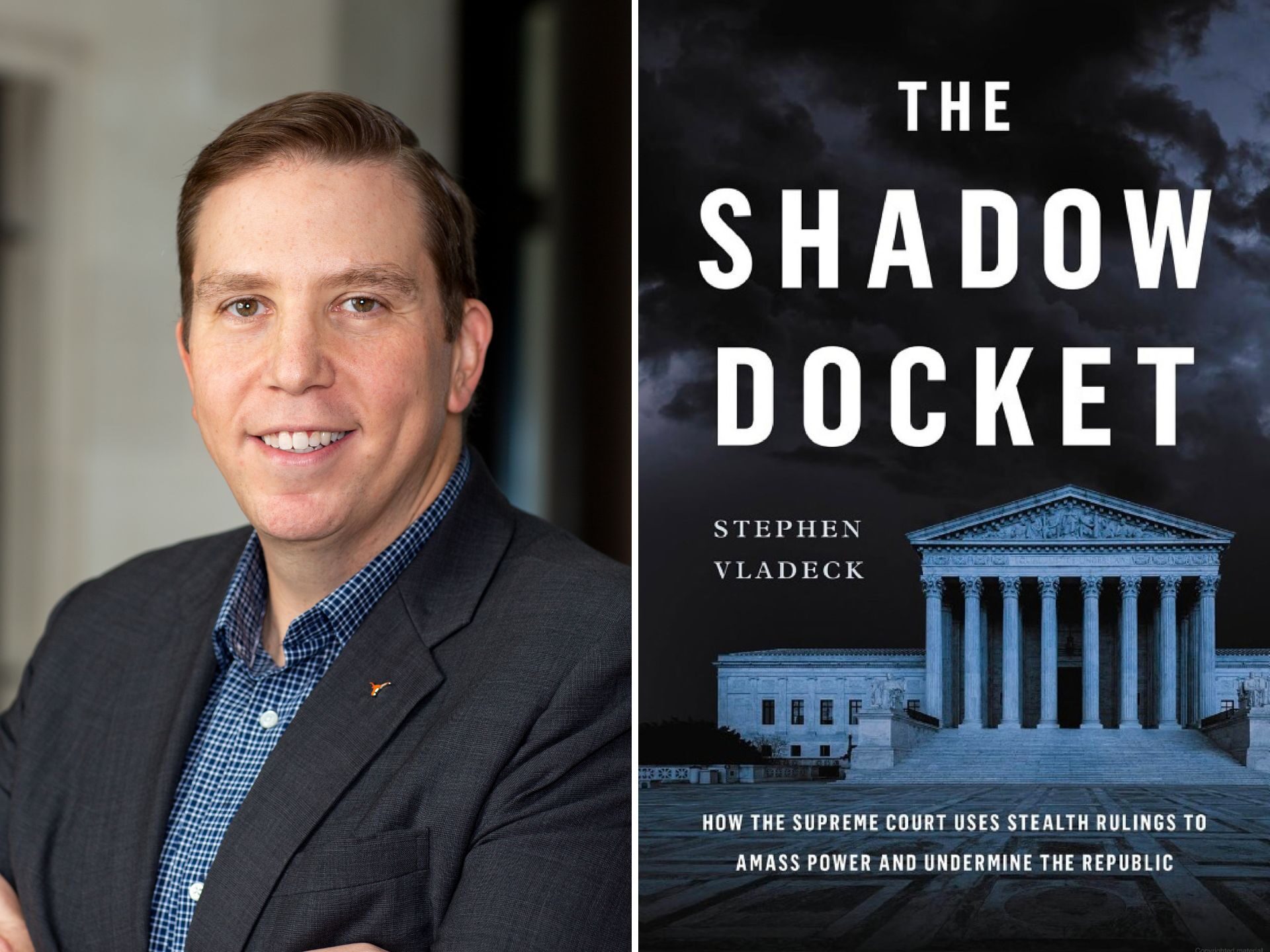

A new book from Texas Law Professor Stephen Vladeck offers readers from the public and the legal profession new historical and critical insights into the U.S. Supreme Court.

Vladeck is a nationally recognized expert on the federal courts, constitutional and national security law, and military justice. His recent New York Times best seller, “The Shadow Docket: How the Supreme Court Uses Stealth Rulings to Amass Power and Undermine the Republic,” has received critical acclaim. In the book, Vladeck closely examines the Court’s stealth rulings that bypass the full briefing and hearing process given to a formal opinion.

Since the book was published in May, Vladeck—the Charles Alan Wright Chair in Federal Courts—has maneuvered a hectic schedule that has featured numerous live appearances, media interviews, and book signings. In Austin, San Francisco, Seattle, Washington, D.C., and New York City, and on CNN, MSNBC, and PBS, he has connected with audiences around the country throughout the summer. This fall, he will continue that reach with multiple public lectures and events both in Austin and nationwide.

On Friday, Aug. 25, Vladeck’s tour will see him featured at the Texas Law “Bookfest” at noon in the Sheffield-Massey Room in Townes Hall.

Vladeck, who also is CNN’s Supreme Court analyst and author of the weekly Supreme Court newsletter, “One First,” recently shared more about his work and future plans, along with observations on the nation’s highest court.

You had been writing about the shadow docket in law review articles, op-eds, and on social media. When did you first say to yourself, “I think this is a book”?

After my first long-form piece on the subject for the Harvard Law Review’s annual Supreme Court issue in November 2019, I knew I hadn’t even begun to scratch the surface of what I wanted to say about the topic. Into that winter and the next spring, I kept coming back to it as the Supreme Court kept issuing more—and more significant—forms of emergency relief through unsigned and usually unexplained orders. And by the summer of 2020, COVID had provided yet another series of data points—cases that made it increasingly clear that the phenomenon I thought I was seeing was not limited, as my earlier work had been, to disputes involving the Trump administration.

I didn’t know what the book was yet, but I knew it was worth trying to translate, to lawyers and non-lawyers alike, why these decisions were so significant—and why the Court’s systematic behavior in these cases was so problematic. So, I used the 2020–21 academic year to sharpen the idea and put together a proposal, with a huge assist from my research assistants and spring 2021 seminar students. By August 2021, one month before the SB8 ruling put the “shadow docket” onto so many radars, we were under contract with Basic Books to publish it.

Another of your keen interests is “forum shopping,” along with its close relative, “judge shopping.”

Any legal system with permissive rules about where lawsuits can be filed is going to incentivize “forum shopping”—where litigants seek to have a case brought in a court that, whether due to the overall lean of the bench, local procedural or substantive rules, or something about the jury pool, is thought to be relatively more favorable than other courts. “Judge shopping” is a more specific—and, in my view, more problematic and less inevitable—variant, in which litigants in some jurisdictions, including a bunch of Texas federal district courts, literally pick the specific judge who will hear their case simply by filing in a particular geographic location.

How does that work in practice?

Because of quirks in how Texas’s four federal district courts and some others subdivide their caseloads, Texas has brought many of its suits challenging President Biden’s administration policies in Amarillo or Victoria—even though those Texas cities have no special connection to the underlying subject matter of any of those disputes. Ditto for the litigation challenging nationwide access to mifepristone, which was also funneled to Amarillo. In an age of nationwide injunctions, if you know you can direct a challenge to a nationwide policy to a specific judge likely to be hostile to that policy and/or the President who promulgated it, you can really distort the legal system in ways that I think are anathema to basic principles of equal justice and the rule of law.

And with this ability to manipulate the system, it’s no wonder that we’ve seen so many more nationwide injunctions issuing in recent years—relief that raises the stakes of government requests for emergency relief, since the nationwide status quo now hangs in the balance. To tie these threads together, at least part of the reason why the Supreme Court is being asked to intervene so much more often these days at such earlier stages of litigation is because it has become easier for those challenging federal policies to obtain hostile rulings from outlier district judges. And judge shopping is a huge part of that.

Who’s the target audience for your book? Where can you exert the most leverage?

I really hope the book impacts several constituencies, but in different ways. For the public, the principal goal of the book is to educate—to help folks who care about the Court and its impact on our lives understand just how we got to this current moment with respect to the Court’s power as an institution, how our current state is not inevitable, and why it’s so important, when talking and thinking about the Court, to look at everything the Court does—and not just the small subset represented by each term’s merits cases.

I also hope the book resonates at least a bit with lawyers, judges, and perhaps even justices—at least in part as a history lesson, but also as an attempt to comprehensively document a practice that has typically been experienced only anecdotally. It’s easy enough to dismiss or defend the Supreme Court’s behavior on a case-by-case basis; it’s much harder when you put all these decisions alongside each other.

And for policymakers, my goal is to remind them that, historically, Congress regularly assumed not just the ability but the responsibility to use its various authorities vis-à-vis the Court as levers—to keep the Supreme Court from getting too out of line and from becoming too powerful and unaccountable. As the separation of parties has become more important than the separation of powers in Washington, that understanding has faded.

But maybe this book will help suggest why it’s so important, whatever one’s politics, for our institutions of government to robustly check each other. And if nothing else, I fervently hope that we can all spend more time thinking, talking, and teaching about the Supreme Court not just as the sum of its merits docket, but as a holistic institution that’s part of a broader interbranch dynamic.

Your Texas Law student research assistants have been closely involved in the book, and in so much of your scholarly corpus. How have they contributed to what you’re doing?

My students were central to this project to a degree unlike any other in which I’ve ever been involved. It’s not just that I’ve had a battery of excellent and dedicated research assistants all the way through. Two different upper-level seminar classes, one in spring 2021 and one in fall 2022, were instrumental in getting the book first off the ground and then to the finish line.

The spring seminar was one of the best pedagogical experiences of my career. We had no syllabus. We’d spent the last 20 minutes of each class talking about what might be the natural next thing to read—so that the students and I organically experienced how the descriptive and normative arguments should be unpacked.

The fall seminar was as good an editing experience as I’ve had, with comments ranging from excellent substantive suggestions to saving me from making embarrassing mistakes in the text.

I named each and every one of these students in the acknowledgements section. They all deserved it. Indeed, one of the reasons why I’m excited to think about the next book is the chance to try this same model again.

Most of your media appearances involve expert commentary or analysis on what someone else said or did. So, how has the experience of promoting your own book been?

It was equal parts exhilarating and discomfiting to be the subject of the media attention. But it was also amazing to get to see so many people in so many different forums who were interested in—and helped to raise the profile of—the book. Periodically, I just had to pinch myself to remind myself that all of it was really happening. The first day of the media blitz in New York—which started on set at CNN at 6 a.m. and ended on set with Rachel Maddow a little before 10 p.m.—was one of the most enjoyable and enervating days of my career, if not my life, and a concentrated microcosm for much of what’s followed.

When this all settles down, what’s next for Steve Vladeck?

I really enjoyed almost all the writing, publishing, and marketing of this book, and I definitely want to try it again. That said, writing about a topic that was literally evolving by the day was, at many points, quite a challenge. It’s hard to shoot at a moving target—or to accept that there’s a date past which the book can no longer be current.

My next project might be a bit more historical and less tied to current events. The two topics I keep coming back to are the election of 1864, which marked the only time in world history that a democracy held a national election in the middle of a civil war, and the Supreme Court’s solidification of its substantive power—and not just jurisdictional authority—during and after Reconstruction. But I’m nowhere close to having anything as fully fleshed out now as “The Shadow Docket” was three years ago, so stay tuned.